Introduction

In the Eastern Mediterranean, a constellation of Greek Aegean islands–Lesvos, Leros, Chios, Samos, and Kos–has become a frontline of EU migration and border enforcement, a ‘hotspot’ where sovereignty clashes with people’s mobility. On each of these five islands, reception centres were established to manage migration by identifying, registering and processing migrants upon arrival. The aim of the ‘hotspot approach’ was to contain and ‘filter’ asylum seekers on the Aegean islands, away from the Greek mainland and Schengen area (Ayata, Cupers, Pagano, Fyssa, and Dia, 2021; Mountz, 2011). This creates border landscapes, 'borderscapes', that epitomise the negotiation between people’s mobility and the EU’s desire to limit migration. Between 2016 and 2019, these centres shifted from administrative ‘detention’ facilities to ‘humanitarian’ camp-like facilities due to the influx of arrivals and the facilities' limited capacity (Painter, Vradis and Papada 2018; Pollozek and Passoth 2019). This article explores how these borderscapes are portrayed and mapped. State maps of these borderscapes, whether created or merely utilised by the state, typically emphasise rigid boundaries and often ignore the fluid, lived geographies of those traversing these spaces. One facility director even compared the layout and map of the centre to that of an airport. Yet, critical cartographers remind us that mapping is never ‘neutral'; they link geographic (cartographic) knowledge with power, making mapping inherently political (Crampton and Krygier 2005, p. 11). Similarly, Harley’s work suggests that maps encode power, ideology and surveillance and that mapmakers are ‘ethically responsible for the effects of these maps’ (Harley 1989). This means that state-centric maps often reinforce dominant narratives—typically favouring the state—while silencing ‘other’ perspectives (Van Houtum and Van Naerssen 2002). In this study, a method was developed to counter those measures, creating a bottom-up approach to state-centric top-down maps. Many scholars, especially in the 90’s, have explored ways to map more than just what is static; they aim to introduce counter and participatory approaches to mapping (Mascarenhas and Kumar 1991; Orlove 1991; Conklin and Graham 1995; Peluso 1995; Rocheleau 1995; Sparke 1995; Albert 1998; Fox 1998; Kosek 1998).

Building on these echoes, I adopted a participatory counter-mapping approach to reveal the hidden spatial narratives of borderscapes, which, in my case, become ‘campscapes’. (Campos-Delgado 2018; Tazzioli and Garelli, 2019; Pezzoni, 2020; Ceola, 2023). In recent years, mapping has ‘slipped from the control of powerful elites’ (Crampton and Krygier 2005, p. 12), and become accessible to ordinary people (Harley 2008). New technologies and open-source tools have democratised mapmaking, enabling anyone with an internet connection to produce maps (Mascarenhas and Kumar 1991; Chambers 2006). From a critical viewpoint, maps should be situated within specific power relations rather than treated as neutral ‘scientific’ documents; critical cartographers note that if maps are understood as power-knowledge claims (Harley 2008), then not only states but also ‘others could make competing and equally powerful claims’ (Crampton and Krygier 2005). In effect, grassroots mapping and scholarly critique have produced an ‘undisciplined cartography’ that is ‘freed from the confines of the academic and opened up to the people’ (Crampton and Krygier 2005). My work here aligns with this vein: I worked with asylum seekers and local stakeholders as mapmakers and creators, inviting them to draw the spaces and routes that mattered to them.

This article presents some of the findings from ten months of ethnographic fieldwork conducted in 2019 and 2022 on the islands of Lesvos, Leros, Chios, Samos and Kos. Through interviews and participatory mapping exercises, I gathered the spatial stories of migrants and, in some cases, staff who are usually left out of official narratives. For example, participants on Leros traced footpaths through inner roads to avoid patrols, while those on Samos mapped hidden ridges and abandoned structures that served as makeshift waypoints. In each case, maps created by participants exposed alternative geographies–routes of survival’ (Anonymised Interview, Samos 2019), that official cartography ignores (Kosek 1998, p. 5). As one asylum-seeker migrant on Leros put it after sketching a dotted line through the hills: ‘The officers patrol the main road, but they do not see the path I take, or maybe they do not want to see’ (Anonymised Interview, Leros 2022). These maps and narratives make concrete the ‘autonomy of migration’ (Tazzioli and Garelli 2019), by showing how migrants navigate and reshape space by transgressing both spatial, physical and political boundaries.

My contribution is as follows: First, I expand critical cartography by documenting how migrants in reception facilities and border spaces generate new spatial knowledge through counter-mapping, thereby challenging the dominance of official state maps and their narrow depictions. Participatory and counter-mapping offer alternative spatial representations absent from official state maps (Quiquivix 2014; Campos-Delgado 2018; Kollektiv orangotango+ 2018). By handing the pen to migrants, I surface the power-knowledge claims that are usually hidden. Secondly, I offer a spatially grounded ethnography of border- and camp- ‘scapes’, from the perspective of those who must navigate them. In analysing these maps and interviews, I engage concepts of ‘sovereignty’, ‘informality’ and ‘the camp as a political space’ (Arendt 1973; Agamben 1998; Ramadan 2012). I show how migrants’ own cartographies contest or complement state efforts at border governance by mapping their spatial realities (Kosek 1998; Chapin Lamb and Threlkeld 2005; Sletto 2009; Quiquivix 2014). Finally, I reflect on how this method–integrating participatory mapping into ethnography–enriches the understanding of borderscapes and yields policy-relevant insights related to border governance (Orlove 1993). The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: the next section reviews the literature on critical cartography, counter-mapping, migration and border studies; the methodology section details our fieldwork and mapping processes; the findings section presents participants’ spatial narratives; the discussion situates the findings within a broader theoretical context and the conclusion highlights the advantage of practising mapping ‘with’ migrants rather than ‘about’ them.

From State Lines to Counter-Maps: A Critical Cartographic Lens

Critical cartography teaches us that all maps are political, not simply objective mirrors of reality. Foundational works such as Wood and Fels’s influential The Power of Maps (1992), first drew attention to how maps ‘express interests that are often hidden’ (Wood and Fels 1992), inspiring many subsequent counter-mapping initiatives. They argued that although maps often serve dominant agendas, making these agendas explicit enables their repurposing for emancipatory aims (Wood and Fels 1992). Crampton and Krygier (2005) similarly critique the assumed neutrality of maps, suggesting that critical cartography is a ‘one-two punch’ of new mapping practices and theoretical critique. By combining open-source innovations with reflexive scholarship, these authors demonstrate that mapping always involves ethical and political choices, demanding heightened awareness of how power relations become inscribed on space (Chambers 2006). Brian Harley’s (2008) seminal arguments reinforce this perspective by showing how technical decisions (e.g., projection, symbology, labelling) encode ideological effects; as Harley (2008) insisted, cartographers hold ethical responsibility for the consequences of their representations.

Against this backdrop, multiple scholars have examined counter-mapping as a direct response to official cartographies, highlighting how marginalised or subaltern groups redefine how space is visualised (Walker and Peters 2001). Sparke (1995), Cobarrubias Casas-Cortés, Aparicio, and Pickles (2006), and many others, describe how activists resist formal state borders by creating alternative maps that ‘delete the border’ or expose its human toll. Likewise, ‘participatory GIS (geographic information systems)’ and community-based efforts have proliferated: Weiner, Harris and Craig (2002) document the expansion of GIS ‘outside the academy’ into community hands, while others illustrate how people’s personal, emotional (Deitz, Notley, Catanzaro, Third, and Sandbach 2018), and cultural understandings of place can be inscribed onto maps (Kingsolver, Boissière, Padmanaba, Sadjunin, and Balasundaram 2017). When harnessed for community-driven initiatives, maps become vital tools for revealing lived realities invisible to official cartography (Peluso 1995). Indeed, work on storytelling maps shows how participants often annotate spaces with subjective meanings—like ‘healing’ gardens or ‘fearful’ corridors—that state or institutional maps would typically omit (Peluso 1995; Campos-Delgado 2018; Musiol 2020).

Building on these theoretical premises, participatory mapping and counter-maps cannot simply be understood as straightforward, instrumental challenges to state authority (Chapin, Lamb and Threlkeld 2005). Instead, they represent cultural productions entangled with contested narratives of identity, authenticity and boundary-making. Drawing explicitly on Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony and postmodern geopolitical frameworks (Albert 1998, p. 59), Sletto argues that boundaries in participatory maps are best seen as sites of discursive struggle and shifting symbolic significance rather than fixed spatial markers (Sletto 2009). Such boundary-making is inherently tied to the political production of space and identity, where maps emerge as dynamic arenas through which contested meanings of indigeneity and authenticity are performed and negotiated (Conklin and Graham 1995; Crehan 2002, p. 1; Radcliffe and Westwood, 2005).

These critical and participatory mapping approaches align closely with discussions of borders and migration, where power asymmetries are pronounced. In postcolonial contexts, state-produced maps and border regimes often perpetuate colonial logic, flattening lived experiences and reinforcing nationalistic projects (Boatcă 2021). Scholars like Quiquivix (2014) stress that cartographic undertakings can either silence subaltern voices or be reclaimed by migrants to assert visibility. This resonates with Walters’ (2006) observation that states extend their sovereignty in zones of exception, including refugee camps. Yet migrants frequently subvert or reconfigure official geographies. The ‘autonomy of migration’ framework (Mezzadra, 2011; Scheel 2013, 2013b; Casas-Cortes, Cobarrubias and Pickles 2015; De Genova 2017) underscores how people on the move exercise agency, constructing their own routes and networks. In this sense, maps drawn by migrants—whether indicating safe houses, clandestine paths or shared community spaces—embody an alternative spatial knowledge that eludes official cartographies (Bryant 2021).

Sletto further expands on the ‘(in)visibility’ and functionality of boundaries, which are strategically manipulated both by Indigenous groups and state actors, reflecting deeper fractures in state authority (Sletto 2009). Invisible boundaries, such as informal community agreements or temporary land-use areas, can often exert greater control and influence over community practices than visible, official state boundaries (Schroeder and Hodgson 2002; Walker and Peters 2001). Thus, participatory mapping processes can inadvertently solidify fluid spatial practices, potentially undermining traditional community dynamics even as they empower marginalised groups (Fox 1998; Fox, Suryanata, Hershock, and Pramono 2016)

Indeed, refugee camps themselves illustrate the tension between state attempts to compartmentalise and the realities of everyday life. Building on Agamben’s ‘state of exception’, migration scholars, for example, Malkki (1995) and De Genova (2016), note that camps can become sites of protest, solidarity, and cultural life. Tazzioli and Garelli (2019) point to how official mapping of camps typically highlights fences, administrative zones and population counts, failing to capture community-organised kitchens, prayer areas or improvised recreational zones. By contrast, ‘counter-maps’ of camps—created by refugees themselves—offer layered narratives of personal histories, social connections, and survival strategies. As Quiquivix (2014) and Bryant (2021) show, such maps are acts of resistance: by naming unofficial trails and social hubs, refugees assert their own sense of place and challenge the bureaucratic logic that frames them solely as ‘managed populations’.

Several studies have leveraged ‘participatory mapping’ in refugee and migration contexts (Fox 1998; Offen 2005; Fox, Suryanata, Hershock, and Pramono 2016). Bryant’s (2021) exploration of migrants’ drawn routes in Europe similarly highlights border control’s blind spots, underscoring that migrants possess critical spatial knowledge about ‘safe’ and ‘dangerous’ sites. Although much of this work relies on digital platforms, there remains a need for on-site, analogue and ethnographic mapping engagements. Moreover, few studies foreground the affective, emotional and social content of migrant maps—categories such as memory, ritual or social ties often remain absent. Here, Lynch’s (1960) notion of ‘imageable environments’ is instructive: as people navigate spaces, they form mental images grounded in symbolic landmarks and key paths. In refugee camps or border sites, these landmarks might be places of worship or makeshift soccer fields—crucially important yet invisible on administrative blueprints (Pezzoni 2020).

This foregrounding of everyday cartographies underscores how mapping can function as an ‘ethnographic method’ (Orlove 1991, pp. 3–38; 1993, pp. 22–46). Scholars in anthropology and geography have long recognised the value of ‘spatial ethnography’, where ‘cognitive mapping’ (Fox 1998) or community-based cartographic exercises supplement interviews and participant observation (Jorgensen 1989; Pink, Leder-Mackley and Hackett 2015; Brinkmann and Kvale 2018). Harley and Woodward’s (1987) History of Cartography series broadens the very definition of what counts as a map, acknowledging that ‘indigenous, pre-scientific or undisciplined mappings abound in many human cultures’ (Harley and Woodward 1987), and can be just as valid for understanding spatial perceptions. Building on these principles, scholars have advocated for ‘cartographic storytelling’, treating maps as narrative artefacts that encode personal and political histories (Orlove 1993; Musiol 2020). By annotating a shared sheet of paper, participants effectively co-produce knowledge with researchers—a collaborative process that can expose overlooked local geographies while also functioning as an act of subversion.

In summary, the combined scholarship on critical cartography, participatory mapping and migration studies emphasises that maps are much more than technical devices. They are sociopolitical tools that can either uphold dominant frameworks or be utilised to resist them. States use maps to demarcate and manage, from borders that reflect colonial power relations to refugee camps, which are often represented as zones of administration. Migrants, in contrast, generate their own spatial logics that reflect daily struggles, cultural identities and survival tactics. By using counter-mapping and participatory methods, researchers and communities together reveal these hidden or ‘erased’ spatial narratives, thereby pushing back against the flattening tendencies of official cartographies. This study applies these frameworks to the Aegean borderscape, demonstrating how refugee-produced maps not only document everyday life in militarised zones but also reimagine these contested spaces through the perspective of the migrant.

Methodology: Tracing Journeys, Drawing Stories

This study draws on comparative, multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork mainly across five Aegean islands—Lesvos, Leros, Chios, Samos and Kos—carried out over ten months (in 2019 and again in 2022). During this period, I conducted 22 semi-structured interviews and over 70 informal interviews with asylum-seekers from diverse backgrounds, as well as with aid workers, volunteers and a limited number of border officials. Additional interviews were also carried out in the south of Italy (specifically in Sicily) as part of a wider project. Across these sites, I organised more than 20 participatory mapping exercises designed to capture migrants’ lived geographies within and around reception and identification centres (RIC) or newer Closed Controlled Access Centres (CCAC). Here, I must mention that I discovered the participatory mapping method during my early involvement in a broader project aimed at understanding the spatial functioning of asylum reception centres after encountering difficulties accessing these centres.

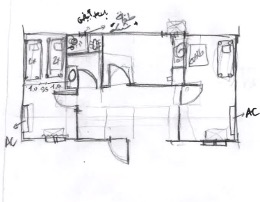

This article attempts to contribute to the scholarship that combines participatory mapping with qualitative ethnography (Lynch 1960; Elwood and Cope 2009; Sletto 2009; Burgess 2011; Downs and Stea, 2011; Kim, 2015; Deitz, Notley, Catanzaro, Third, and Sandbach, 2018; Laituri, Luizza, Hoover, and Allegretti 2023). In each exercise, I employed adaptable mapping ranging from simple to structured formats to accommodate varying scales and spatial narratives. The rationale behind this flexibility was to allow participants to choose the scale at which they wanted to represent their experiences, whether it be the specific unit they inhabited, the broader camp or facility or even the entire island. The mapping exercises thus included three primary types: (1) ‘blank outline’ maps depicting basic boundaries of the site (such as camp perimetres, main landmarks, highways and entrances) and providing participants with a simple framework to annotate freely (see Figure 6); (2) ‘satellite images with transparent overlays’, enabling detailed geographical referencing via transparent sheets laid over high-resolution satellite images to annotate and update spatial features, highlight recent changes or precisely trace routes from one point to another (see Figures 1 and 4); and, at times, (3) ‘completely blank pages’, which gave participants the freedom to express their spatial stories and scale without any predetermined boundaries or constraints (see figures 2, 3 and 5). This latter approach facilitated narratives that could shift fluidly across various scales and geographies, allowing participants full control over the spatial representation of their lived realities.

Participants used pens, markers and coloured stickers to identify routes, settlements, landmarks and zones of personal significance. I asked guiding questions such as, ‘Walk me through your day—where do you go usually?’ As participants annotated their maps, I probed with follow-up questions: ‘Why did you mark this path?’ and ‘What happens in this particular spot?’

These mapping sessions typically lasted one to two hours. Most were conducted on an individual basis, although occasionally small groups, such as families or close friends, chose to collaborate on a single map. The mapping exercises were facilitated in English, French or Arabic, depending on participants’ preferences, including mine. All participants provided informed consent, and pseudonyms are used in this paper to safeguard their identities.

Semi-structured and informal interviews complemented the mapping component. When a participant drew a particular route or zone, I would ask them to explain its significance. In many cases, participants traced their broader journeys onto an outline or satellite map, pointing out key transitions and obstacles such as trails, checkpoints or safe houses. Interviews were audio-recorded (with permission) and later transcribed. In sessions where recording was not feasible or if the participant did not wish to be recorded, I relied on handwritten notes for documentation.

Beyond the organised mapping and interview sessions, I also participated in observational tours of each camp (when granted permission) and held informal conversations both inside and outside the camp in communal areas such as cafes, recreational spaces, courtyards, bus stations and at camp gates. These observations helped triangulate data from the participatory maps and allowed me to note inconsistencies between official camp layouts and participants’ experiences. Field notes and reflexive memos documented these observations, especially how participants interacted with the maps, which sometimes became sites of contestation over the naming or labelling of particular locations.

All qualitative data, such as transcribed interviews, photographs of annotated maps, and field notes were organised and coded thematically. Thematically, I focused on routes of mobility, informal social spaces, practices of resistance or evading control and affective ‘safe’ or ‘dangerous’ zones. Particular attention was paid to discrepancies between official camp schematics and participants’ own renderings. For instance, participants often drew hidden shortcuts or holes in the fence or relabelled places with names of their own, thus revealing unofficial geographies that official maps either overlooked or purposely omitted.

Where multiple participants consistently identified the same clandestine paths or described similar coping strategies, I compiled these convergent data points into digitised composites. In analysing these maps alongside interview transcripts, I maintained a close link between drawn features and participants’ own words. For example, if a participant traced a dotted line across a hill and explained, ‘I go through here at night to avoid the guards’(Anonymised Interview, Lesvos 2019), the dotted line was coded in the ‘mobility/resistance’ category, and I cross-referenced that statement with any corroborating accounts from other participants.

This combined approach of spatial ethnography through participatory mapping and in-depth interviews was chosen to foreground participant-led knowledge production. Rather than merely geocoding narrative interviews, I treated the very act of co-creating maps as a rich ethnographic encounter. Mapping elicited tacit knowledge that might remain unstated in a standard interview, and it often empowered participants by giving them a tool to articulate their own spatial logics.

In line with critical and participatory approaches, the methodology prioritises embodied, on-site engagement. The extended field presence across multiple islands enabled me to observe how everyday movement patterns and social relations materialise in camp environments that are otherwise bureaucratically defined. By systematically coding and comparing both the ‘stories behind the marks’ and the visible features drawn on the maps, the research yields insights that a solely interview-based or remote mapping approach might miss. This triangulation underscores the camps as contested spaces, simultaneously governed by state logic and shaped by the agency of those who inhabit them.

In sum, the methodological design integrates participatory mapping with traditional ethnographic techniques, ensuring that the visual and spatial data gathered reflect participants’ lived experiences. The trust built through mapping sessions, combined with the depth of interviews and field observations, gave a deeper insight into how asylum-seekers navigate, reconfigure and resist the borderscapes of the Aegean islands.

Findings: Unveiling Hidden Spatial Narratives

Analysis of the participatory maps and interview data revealed that official cartographic representations of the Aegean Reception and Identification Centres (RIC) or the newer Closed Controlled Access Centres (CCAC), diverge markedly from migrants’ lived geographies. Rather than static, bounded sites of control, the camps and surrounding areas emerged as dense networks of hidden routes, informal social spaces and deeply affective landscapes. I present these findings under five interrelated themes.

Hidden mobility networks frequently emerged in participants’ maps, as evident in the prevalence of unofficial paths such as ‘shortcut’ trails, fence holes, or diagonal routes circumventing official checkpoints. While state diagrams typically depict a small set of authorised roads and gates, the counter-maps showed a broader, more fluid topography. On Samos, for instance, a young man marked a winding trail on the northern ridge, indicating how they avoid detection when moving in and out of the camp. Several participants on Lesvos annotated a fence gap they use to reach showers or stores without enduring lengthy security checks. He stated, ‘I don’t want to wait three hours every time just to take a shower’ (Anonymised Interview, Lesvos 2019). These ‘desire lines’ reveal that governance is porous: even though fences and checkpoints project power, migrants constantly renegotiate these boundaries in practice.

Camp landscapes came into focus as lived spaces through participants’ annotations, which depicted dynamic, subdivided areas inhabited by multiple actors such as residents, NGO staff, volunteers and, at times, overlapping layers of local, national and EU authorities. In several workshops, participants meticulously mapped the various flows within the camp. One staff member sketched the ‘official path’ taken by new arrivals through security checks and registration tents, then drew arrows around the camp perimeter to illustrate the actual, inconsistent flow of people and responsibilities (Anonymised Interview 2019). They labelled these lines ‘the real flow’, explaining that NGOs and volunteers often step in for official agencies, while EU border forces sometimes overlap with local police. Another participant highlighted a protest site inside the camp, emphasising that, despite intense surveillance, the camp remains a contested arena where migrants organise collective action or simply carve out small spaces of relative autonomy.

Informal social spaces were also prominent in the counter-maps, revealing meaningful places that do not appear on official diagrams. Participants highlighted self-created communal areas—unofficial markets, gardens, improvised ovens or quiet corners used for conversation and prayer. One participant on Lesvos labelled a spot near the camp fence where residents built a makeshift stone oven to bake bread reminiscent of their homeland, remarking, ‘I like the bread I know’ (Anonymised Interview, Lesvos 2019). Others pointed to hidden gardens or memorial sites tucked behind tents. Despite the camps’ restrictive design, these ‘off the map’ locations become vital for maintaining cultural practices, sustaining social ties and fostering a sense of normalcy. Though fragile, such informal spaces often carry strong emotional weight—a hidden corner to share tea may mean more than a large cafeteria run by external agencies.

Resistance and evasion tactics were equally integral to the maps. Participants sometimes crossed out guard towers and police posts or marked them with red X’s to signify fear or avoidance. One man on Lesvos circled the main checkpoint and drew an arrow to a gap in the fence, noting, ‘I use this hole in the fence every day to avoid security checks’ (Anonymised Interview, Lesvos 2019). Groups of participants often described gathering in olive groves to exchange goods and information, illustrating that state formal control extends through numerous, seemingly minor sites, but is undercut by everyday, small-scale manoeuvres. For migrants, charting these subversions serves as both a practical aid to survival and a testament to their agency within a system designed to contain them.

Emotional and sensory geographies surfaced strongly through participants’ recollections, revealing an intensely affective dimension of camp life. While official schematics might record only a burned building or empty container, participants recounted personal stories behind these places, such as neighbours rescuing each other from fires or a makeshift school where children once gathered before relocation. Some annotated their maps referencing smoke, sewage or other sensory markers, while others highlighted memory sites that triggered trauma or solidarity. One person from Samos described feeling freer when living in the informal ‘jungle’ near the camp in 2019, before being moved to a more restrictive facility in 2022, and marked the overgrown area with the note: ‘Back then, I could breathe’ (Anonymised Interview, Samos 2022). This recalls Lynch’s ‘imageable environments’, underscoring how individuals create mental maps rich in personal meaning (Lynch 1960).

Bringing these counter-maps to light underscores how official depictions of Aegean migrant facilities fail to capture the multiplicity of experiences unfolding within and around them. Where states perceive fences, prefabricated container units and administrative offices, migrants identify alternative routes, contested borders and vibrant community spaces. By overlaying and comparing these contrasting narratives, one sees how the ‘official’ borderscape is continuously reshaped through everyday acts of navigation, resistance and the drive to uphold personal and cultural identities. As one participant in Lesvos put it, ‘The government’s map is just a rectangle. Our map is our heart’ (Anonymised Interview, Lesvos 2019). This comment encapsulates the power of participatory mapping to reveal the social worlds that people forge, even in the most constrained environments.

Discussion:

By situating migrants’ spatial knowledge and everyday practices at its core, this study illuminates the gap between official representations and on-the-ground experiences. Below, I discuss these findings in relation to questions of sovereignty, informal spatial practices, and the broader theoretical and methodological implications for critical cartography and border studies.

As my participatory mapping results have shown, migrants are contesting border governance by layering hidden paths and informal routes, thereby underscoring how porous and negotiable state authority can be (Campos-Delgado 2018). Each line drawn away from a guarded road exemplifies migrant autonomy, giving material form to ‘autonomy of migration’ scholarship. These findings reveal that sovereignty in such settings is not monolithic; rather, it is subject to ongoing negotiation among authorities, NGOs, smugglers and migrants themselves. The camps, intended as instruments of control, thus become arenas where migrants redefine space according to their survival strategies.

This became especially apparent through the informal spatial practices and everyday survival strategies of the migrants, as participants’ annotations underscored how individuals and communities create parallel geographies of support by navigating farmland shortcuts, hidden goat tracks or unregulated meeting places. These informal routes, rather than random or chaotic, reflect accumulated knowledge about local terrain, safe passage or accessible resources. This co-construction of space from below challenges top-down assumptions that camp environments can be wholly controlled. Indeed, the presence of gardens, communal ovens and improvised gathering spots highlights the micro-economies and mutual support systems that flourish despite restrictive policies. From a practical standpoint, these invisible geographies point to potential policy intersections: humanitarian actors could coordinate with local knowledge to better place resources while recognising that any engagement must remain mindful of the potential for increased surveillance or unintended harm.

Looking beyond its administrative functions, the maps reveal the camp (especially at the borders) as a contested political-spatial construct shaped by community gathering points, protest sites and improvised ‘safe’ areas. The maps also advance our understanding of the camp as more than an administrative zone. Although official representations often emphasise functional areas, gates, fences and bureaucratic flows, participants’ drawn lines and annotations reveal a more internal order, populated by community gathering points, protest sites and improvised ‘safe’ areas. These coexisting logics emphasise the hybrid nature of camps as both an extension of state sovereignty and spaces of negotiated power. Residents, NGOs and authorities co-shape these geographies, sometimes cooperatively, sometimes in conflict. Such insights accord with scholarship that sees camps not merely as instruments of control but also as sites of community and resistance (Tazzioli and Garelli 2019). By showing how migrants carve out religious, educational and social zones (spaces that official site plans often ignore), the maps demonstrate the camp’s capacity to serve as both a site of exclusion and a locus of emergent community life.

As my findings suggest, incorporating mapping into ethnographic interviews not only externalises tacit spatial knowledge but also reshapes the researcher-participant dynamic. Asking participants to ‘draw their story’ externalised details that might have gone unmentioned in a purely verbal format. This confirms existing arguments about the power of participatory cartography to surface tacit spatial knowledge (Fox, Suryanata, Hershock, and Pramono 2016). In many cases, the maps served as dialogic prompts: participants reflected aloud on power structures, recounted personal histories tied to specific locales and challenged official naming practices. Such co-creation also shifts the traditional researcher-participant dynamic, empowering migrants to shape the research process. Nevertheless, it introduces ethical considerations around representation and potential risk—particularly if these maps were to fall into the hands of authorities. The reflexive approach taken here, including anonymising sensitive routes and using pseudonyms, is critical for minimising harm while maintaining the depth of collected data.

Extending these observations, the data shows that multiple actors—states, NGOs, local communities and migrants—continually remake the borderscape through daily negotiations and interactions. Viewed through the lens of critical cartography and migration studies, the findings underscore that borderscapes are socially produced rather than purely imposed from above. Multiple actors—states, NGOs, local communities and migrants—shape these environments through their daily practices and interactions. Maps demonstrate that border governance operates through dispersed, overlapping spheres of influence (Kosek 1998). Overlapping jurisdictions, from EU and UN agencies to local police, create fragmented structures that migrants navigate and sometimes exploit. By adding ‘unofficial’ flows and emotional geographies, counter-maps bring visibility to these negotiations, underscoring that the border is constantly being made and remade.

Counter-maps thus serve as both epistemological and political tools: they document the gaps in official knowledge, while also affirming migrants’ agency in defining and traversing the spaces they inhabit. In highlighting stories of protest, survival and collaboration, the study challenges state-centred visions of order and control. Instead, it portrays a borderscape as an intricate interplay of power, vulnerability, and resilience.

Given the depth of these counter-mapping insights, it is crucial to consider how they might affect both humanitarian interventions and state surveillance. On one hand, officials could, in theory, use local spatial knowledge to improve safety measures or humanitarian provisions in sites migrants already frequent. On the other hand, such knowledge could also be instrumentalised to tighten surveillance—an outcome contrary to the spirit of counter-mapping. Thus, any practical application must remain cognisant of potential harms. More broadly, the visibility afforded by counter-maps can prompt critical reflection among stakeholders about the consequences of treating camps as mere holding facilities rather than dynamic social worlds. By foregrounding the experiences and spatial logics of migrants themselves, this study supports broader calls to move beyond simplistic or securitised representations of borders. It affirms that participatory mapping, coupled with ethnographic engagement, offers a potent methodology for revealing how borders operate in daily life. Rather than a neat line demarcating territory, the border emerges here as a continuously contested field of power and resistance—one that, in the words of one participant, ‘belongs to those who actually live it every day.

Conclusion:

Rethinking Borders Through Collaborative Cartography

This study demonstrates how participatory counter-mapping can serve as a lens for Aegean borderscapes (and beyond), revealing dimensions that state representations overlook. By centring migrants’ lived experiences, it underscores that mapping is never neutral, but rather a means through which power relations, identities and everyday struggles become inscribed on space. In doing so, the findings illuminate the ‘autonomy of migration’, showing that migrants are far from passive subjects: they actively reshape and redefine the spaces they inhabit.

Methodologically, combining participatory mapping with ethnographic inquiry expands our understanding of people’s mobility by uncovering insights into emotional, sensory and communal geographies that remain hidden in purely interview-based or quantitative studies. This layered approach becomes especially clear when analysing the maps drawn by participants who documented shortcuts, fence gaps, and improvised gathering areas, exposing a level of lived complexity that state-centric cartographies ignore. They also highlight camps as more than static, confined zones; they are contested landscapes where migrants create their own routes of survival and shared cultural spaces, such as the makeshift bread ovens described by participants on Lesvos, in direct response to restrictive policies and insufficient resources.

By comparing official maps with the counter-maps, it becomes evident that these sites are far from neatly defined administrative territories. The data underscores how people’s everyday routes, hidden paths and ‘off-map’ gathering spots form a dynamic spatial network shaped by resistance, cultural practice and social bonds. This challenges any notion that camps can be fully controlled by top-down governance. Instead, participants’ narratives reveal a continuously renegotiated terrain in which migrants assert their agency.

At a policy level, the data generated through counter-mapping calls into question a heavy reliance on aerial surveillance or official statistics as the sole basis for decision-making. By incorporating migrants’ own spatial perspectives, such as the young man on Samos who mapped a winding trail to avoid detection, policymakers can gain critical insight into the daily practices, informal routes and communal networks that define life in ‘hotspot’ sites. In turn, this awareness can foster more humane and effective interventions, shifting focus away from militarised control and toward support, safety and respect for autonomy.

Ultimately, these maps remind us that what appears on a ‘state’ map as a rectangle or numbered zone can carry deep personal meaning, including trauma, solidarity and memories of survival. Mapping ‘with’ rather than ‘about’ migrants not only advances scholarship in critical cartography and migration studies, but also provides a tangible record of migrant agency. This record can inform more inclusive and responsive border policies. By unveiling hidden spatial narratives and centring lived experiences, counter-mapping pushes us to rethink how we represent, govern and inhabit these border zones as spaces of both constraint and possibility.