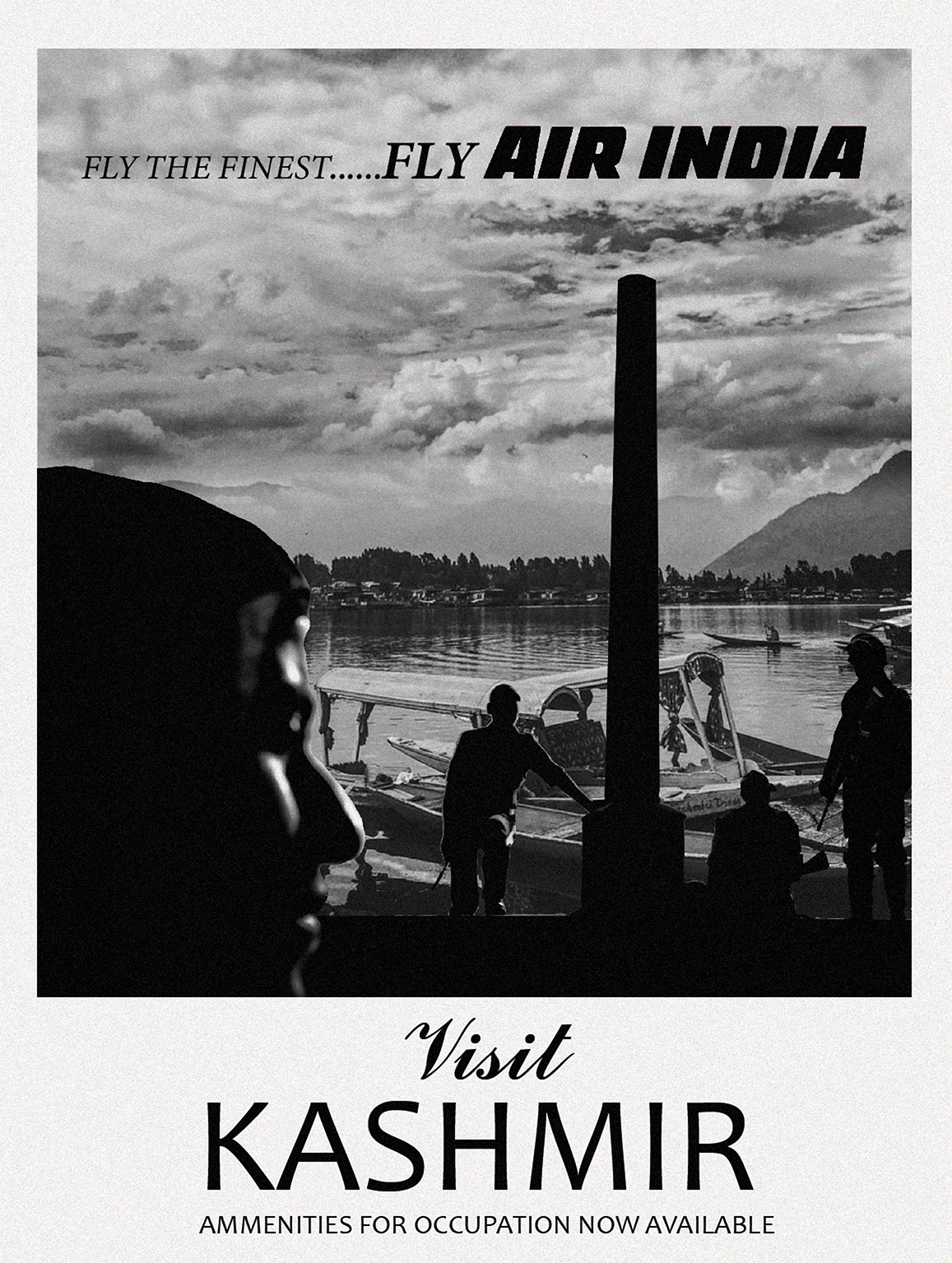

The Military Urbanism

From imperial conquests to colonial rule and now occupation, the perception of conflict has reoriented, positioning itself within the city. Cities, once considered spaces separate from the theatre of conflict, have become primary arenas, rendering physical borders and traditional entry points into cities obsolete. War has entered the city–not war in the city, but war of the city, by the city (Weizman 2003).

Cities have a spatial syntax that is not apparent from above. The aerial perspective, central to early 20th-century military strategy, renders space abstract and controllable, aligning with the occupier’s logic (Weizman 2003). However, in urban warfare, reading the spatial order of a militarised city like Kashmir requires shifting to ground-level perspectives, where daily life, movement and resistance become legible.

The city is now understood as a complex system of interdependent networks where military and resistance networks spatially overlap in the urban battle-space. Those defending their city from the occupier are intimately acquainted with its layout and exploit this knowledge by utilising secret passages, rooftop connections and underground networks (Weizman 2003). Military strategists have come to recognise the importance of understanding this new urban fabric, seeking to manipulate key infrastructure systems for strategic control. This shift has led to the militarisation of civil society, referred to by Stephen Graham as ‘new military urbanism’, where public and private spaces intertwine in a manner that transforms civilians into both targets and perceived threats (Henni 2016). In cities under occupation, this manifests as inflicted spaces–unwelcome environments deliberately reconfigured to impose control through spatial means. These spaces are not the collaterals; they are the architecture of occupation calculated to erode autonomy, reshape collective memory and normalise the presence of power in everyday life.

Democracy within urban space has decreased, along with an unprecedented increase in control over citizens by the military and state institutions.. This militarisation of civil society allows the military to establish new cartographies in previously inaccessible spaces (Schoonderbeek and Shoshan 2016). The sudden emergence of new spaces of conflict has considerably altered architectural discourse as extreme conditions of war and militarisation are structurally reconfiguring our living environments. Perceived as a condition of the contested territories, militarisation has slowly transfixed itself onto the entire globe. It is an interlinked global reality rather than a series of isolated global events, impacting both Western metropolises and burgeoning cities in the Global South (Graham 2011, p. XIII).

In Kashmir, this normalisation of militarisation has transformed everyday life into urban warfare, where architecture and planning function as a technological apparatus aimed at controlling and subjugating the populace. Recent events of intensified lockdowns and communication blackouts following the revocation of the Article 370 and 35A in 2019, illustrate how spatial control is deployed as a tactical tool, turning streets, checkpoints and even basic services into tools of domination. This transformation has profoundly reshaped the urban landscape, embedding fear, insecurity and surveillance into the collective memories of Kashmiris.

A Territory In-between

Kashmir’s contested sovereignty is rooted in the establishment of independent nation-states of India and Pakistan, leading to India’s temporary accession of Kashmir in 1947. India justified its intervention in Kashmir by citing a ‘tribal invasion’(Lamb 1991, p.138). Merely two months after gaining independence, India transformed itself into an occupier by airlifting its military into Srinagar city on 26 October 1947. Ever since, the Indian state has governed the Kashmir Valley as an occupied space, subjecting Kashmiris to a state of permanent arrest, controlled through a vast and highly intrusive military apparatus. This has resulted in the fundamental alteration of public, semi-public and private spaces, producing an extensive network of control and forms of violence that constantly reinforce Indian state’s hold over the region and its citizens.

Through intensive militarisation of Kashmiri society, India administers the Kashmir Valley through a form of civil-military authoritarianism reminiscent of the necropolitical arrangements found in other militarised zones such as Belfast, the West Bank, the Basque region and Chiapas, as well as late modern total institutions like mental asylums, war prisons and refugee camps that confine vulnerable populations who are deemed outcasts (Duschinski 2009, p. 710). Kashmiris have consistently refused to accept Indian control in Kashmir, describing this forced management as ‘Jabri-qabza’ (occupation or forced possession) (Zia 2017).

India has constantly framed Kashmir within secular ideologies, asserting its integral status, while dismissing all self-determination movements by labelling them as secessionist or as Pakistan’s proxy wars. These beliefs shape national identity and history, glorifying and legitimising military actions (Duschinski 2009, p. 696). These beliefs shape national identity and history, glorifying and legitimising military actions (Duschinski 2009, p. 696), from the suppression of the armed struggle for liberation, the 'Al-Fatah movement' of 1965, to counterinsurgency operations against civilians and armed militants after the controversial elections of 1987. The latter action forced the occupation (previously confined to border and cantonments areas) to seep into the urban areas of the Valley. Since 2008, armed militancy has declined and the pro-freedom movement has taken a major turn towards civilian uprisings, including public demonstrations. Yet in the past 35 years, India has escalated its troop presence from 80,000 in January 1990, to over 700,000 in the region. Emergency laws like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) have been implemented in order to tighten the military’s control.

The recent revocation of Articles 370 and 35A in August 2019 by the Indian government unilaterally marked a significant intensification of India’s efforts to integrate Kashmir into its national framework. These articles granted special autonomy to the region’s indigenous population, and their revocation split the historical state into two directly controlled ‘union territories’ (Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act 2019, p. 7), and shifted land control from local to national levels, opening the ‘territories’ to Indian settlers. This has led researchers to analyse the issue through a settler colonial perspective. While it may provide a useful framework for understanding Kashmir and make it comprehensible to a global audience, Mushtaq and Amin (2021) argue that reliance on a future Indian-citizen-settler runs the risk of invisibilising the Indian armed forces already permanently stationed in Kashmir.

Mohamad Junaid, a Kashmiri scholar, describes this militarised process in Kashmir post-1990s as military occupation, characterised by an “ensemble of spatial strategies and violent practices that the occupier state employs to dominate physical space in a region where its rule lacks, or has lost, popular legitimacy” (Junaid 2013, p. 161). The intricate interplay between conflict and space in Kashmir underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted challenges inherent in this militarised urbanism.

Kashmiris have faced 70 years of undemocratic erosion of autonomy, regardless of which political party held power. This process has been enacted through spatial control leading to resistance. In the occupation-induced deterritorialisation since 1947, the native civilian is vulnerable to being considered a suspect and a ‘potential threat to peace’, while the settler celebrates the Indian trooper’s act of ‘guarding’ this very ‘peace’ (Lambert and Mariam Raj 2022, p. 18).

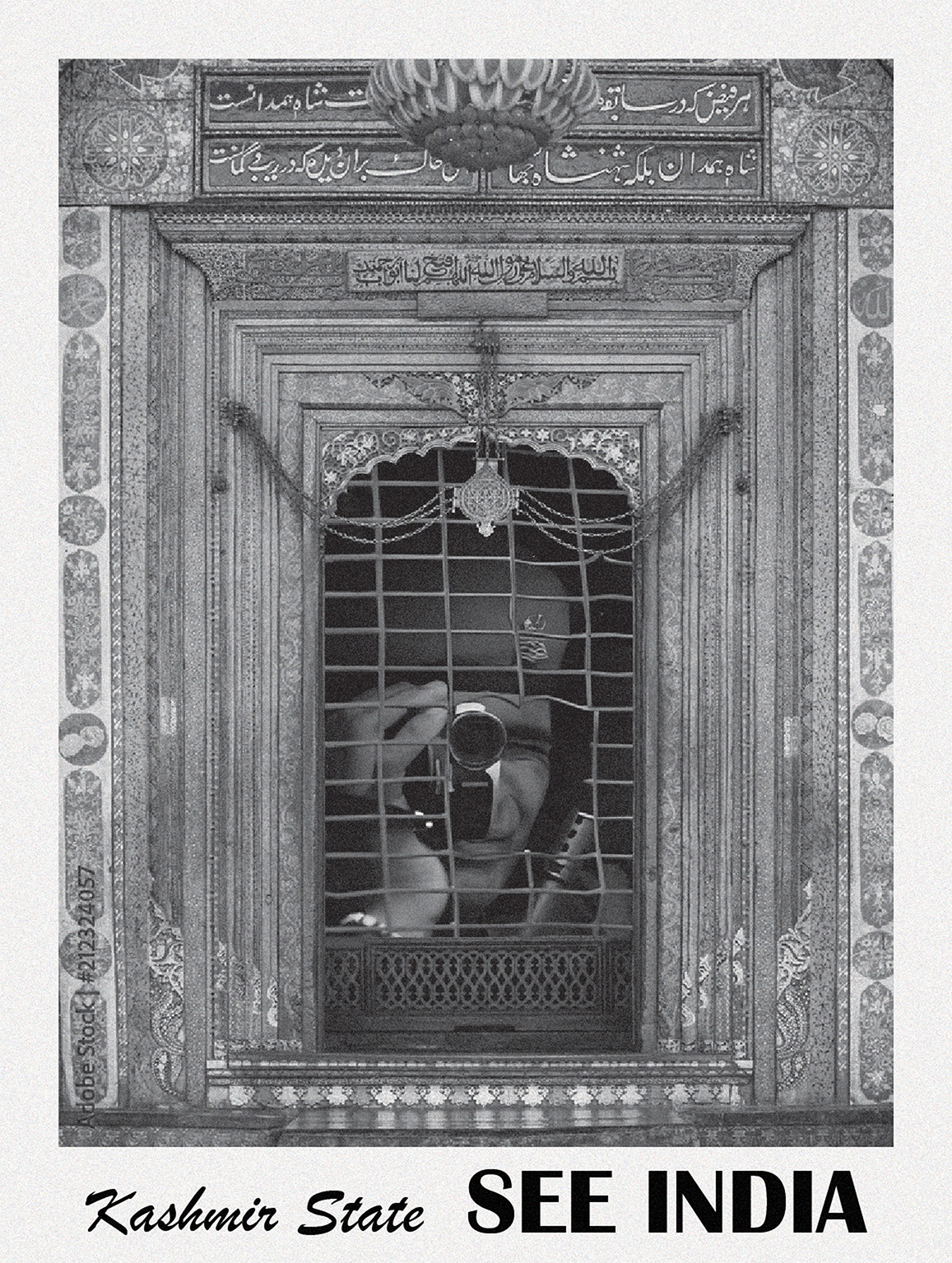

In the context of military occupation having made itself invisible, this research makes visible its effects, namely: the configuration and expression of power through the physical reorganisation of space; the use of architecture and urban elements as tactical tools; and the extensive infrastructure, environments and large-scale military operations that work systematically to produce violent spatial control that constitutes the occupation in Kashmir.

In a time of escalating global conflict, when the legacies of older wars are yet to be resolved, militarisation has converted cities and urban centres into battlefields for contemporary warfare, transforming them into networked entities that are physically unfortified and seemingly borderless (Weizman 2003). This sudden emergence of new spaces of conflict has considerably altered architectural discourse as extreme conditions of war and militarisation have structurally reconfigured our living environments. With concepts like 'urbicide' and 'designed destruction' becoming default strategies on a global scale, cities are turning against their inhabitants (Weizman 2003). This shift raises profound ethical dilemmas for architects and urban planners. Their contributions to the militarisation of cities drive them into a complex terrain filled with challenges. The act of design—whether it involves objects, buildings or entire urban landscapes—parallels the functions of the military. Both endeavours inherently anticipate and encourage specific behaviours (Lambert 2015, p. 4).

The Military Apparatus

The occupation of Algeria by the French military marked the first time that systematic torture and total warfare on local populations was developed, implemented and employed by the military. It was considered total warfare because it not only mobilised a country's industrial, commercial and agricultural powers, but also involved all segments of society, including children, women and the elderly, harnessing their emotions and energies for war efforts. It represented a significant shift in warfare, moving away from conventional battles between two armies on a battlefield to a more intricate system where the target was hardly discernible and therefore the entire population was at risk (Henni 2016, p. 39). Throughout the Algerian occupation, these objectives were pursued through territorial and spatial interventions, including the establishment of new borders, infrastructure development, forced displacement of civilians and the creation of monitoring systems to survey the population deemed as potential threats (Henni 2017).

The term ‘occupation’ has its roots in international humanitarian law and is characterised by the control of territory by a foreign armed force (International Committee of the Red Cross 2015). But military occupation extends beyond mere territorial control; it involves a strategic deployment of architecture and territorial planning to alter the landscape in order to exert state power. It is the 'slow process of building and lengthy bureaucratic mechanisms of planning that are as much a part of the scene on which territorial conflicts are played out’ (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003). Here, architecture and territorial planning are used as 'tactical tools' to exercise the state's power, serving strategic and political agendas (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003, p. 19). This continuous interplay manifests itself as a complex game through observation, the reconfiguration of living environments and the disruption of routine, transforming spaces of everyday life into stages of urban warfare.

'The terrain dictates the nature, intensity, and focal points of confrontation, while conflict itself is manifested most clearly in the processes of transformation, adaptation, construction and obliteration of the landscape and the built environment’ (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003, p. 19). These territorial conflicts unfold not only on these new battlegrounds but also within the intricate realms of planning and administration, shedding light on the multifaceted nature of the occupation.

The military approaches the challenge of controlling a city similarly to how an urban planner tackles development issues. Both aim to exert control over an area by manipulating its infrastructure, altering the physical environment and addressing the cultural dynamics of the local population (Weizman 2003). This militarisation of spaces not only occurs during foreign occupation but also arises due to the erosion of the contract between local government and citizens, leading to internalised occupation or use as a measure of safety between friendly enemies sharing a common space. Studying occupied regions across the globe is vitally important in understanding the occupation in Kashmir and the new world. Each region is unique, emerging from distinct historical backgrounds and localised cultural conditions. Yet, they share a common set of existential factors, contributing to what we might call an ‘emerging global condition’. Whether it's the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories or the security apparatuses in Egypt claiming to safeguard future development, these internal forces often pose risks to the security of citizens. Similarly, in the United States, the 'war on terror' has led to unprecedented levels of surveillance, visible through electronic or physical barriers in office buildings, shopping centres and transport hubs, and spanning from urban centres to suburbs (Graham 2011, p. XL). These measures further reinforce internal city borders, creating local enclaves that impede spatial democracy and freedom. It is crucial to recognise that occupation has architectural dimensions, with territories being architectural constructs that shape how occupation is conceptualised, organised and executed. In analysing various occupations across the globe, it becomes evident that a discernible logic guides the occupation of regions, affecting not only individual cases but also a broad class of cities experiencing tension.

Similar to contested places across the globe, in Kashmir, the ordinary spaces of daily life transform into stages of urban warfare, where architecture assumes the role of a technological apparatus, producing an inflicted space and obstructing the democracy and fair development of Kashmir’s urban and extra-urban areas. Mohamad Junaid contends that this urban condition is not an exceptional wartime measure but ‘a permanent structure of governance, an “ensemble of spatial strategies” that continuously reasserts dominance in a territory where legitimacy is absent’ (Junaid 2013).

For analysis, these are grouped into four interrelated categories: ‘adaptation’, ‘alteration’, ‘transformation’ and ‘construction’, offering insights into how military forces employ territorial and spatial operations to assert control: adaptation refers to the repurposing of existing civilian infrastructure for military use; alteration denotes partial, flexible and temporary changes that disrupt movement and access while preserving the fundamental essence of the system; transformation signifies a comprehensive, often permanent change that fundamentally reconfigures the nature and essence of the built environment to serve security objectives; and construction involves the planning and assembly of physical structures or systems, resulting in new infrastructures designed explicitly to consolidate control.

These four categories examined in this paper are understood as overlapping techniques in time and space, operating across scales, through which the state produces inflicted space, embedding the logic of military control into the urban fabric.

The Kashmir Valley is subjected entirely to military occupation, however, the urban area of Srinagar, the summer capital of the valley, has emerged as the epicentre of resistance. While this section of the text examines the techniques and impact of military occupation throughout the Valley, the primary focus is on Srinagar, with brief references to other districts. It is important to note that the region's occupation imposes significant limitations on the ability to conduct comprehensive studies across the entire area. The intricate interplay between conflict and space in Kashmir underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted challenges inherent in militarised urbanism. Identifying these tactical tools in terms of their intended functions as division, movement, sight and civilianisation, gives a deeper insight into their impact on the spatial dimension.

Adaptation

The swiftness of the uprising in the late 1980s led India to urgently deploy the military in the region. Given the lack of preparation, there was a shortage of adequate housing for soldiers. The military’s response was to occupy any field, property or building they found suitable, embedding themselves within the dense urban fabric. Beyond this logistical necessity, it can also be argued that soldiers were deliberately stationed within civilian areas to quickly establish control, making the military an everyday presence in the Valley’s urban fabric (Junaid 2020). By situating themselves within the heart of the uprising, in residential areas, commercial zones and public spaces, the military conducted (and continues to conduct) surveillance, interrogations and harassment of the residents under the guise of security. This mirrors a growing global trend of the presence of military forces amongst civilian populations.

The Indian military is present in virtually all public spaces in Kashmir, continuously dividing and subdividing the region into military sectors, operational zones and special police ranges. Over decades, numerous camps, cantonments and bunkers have emerged inside schools, hospitals, public buildings and orchards, while public movement is continuously monitored. The camps, cantonments and bunkers also extend to optically strategic sites. In Srinagar, elevated areas like Hari Parbat fort atop Koh-i-Maran (also known as Hari Parbat) Shankaracharya hill and the foothills of the Zabarwan range are all under military control. Overlooking the entire capital city of Srinagar, these sites enable the military to survey and dominate a vast area. Similar to hilltop settlements in the West Bank, these high grounds offer greater strength, self-protection and optical planning. The military also occupies symbolic places in Kashmir. Lal Chowk (red square)—a public square rich in histories of liberation, resistance and counteractions against the Indian state and a site frequently used by resistance groups for marches—is transformed into a bunker and watchtower, surrounded by concertina wire and sandbags (Falak 2023, pp. 69–70). The clock tower, built in the middle of the square in 1980, has now become emblematic of Indian presence.

Most of these sites continue to remain under the military’s control, although many were vacated due to the political pressure following the unrest of 2010 (Vij 2011). The map highlights the temporary yet permanent apparatuses—strategically nestled in corners and infiltrating the valley—that were or are under military control.

Alteration

In occupied territories, control is exerted over space by an extensive surveillance infrastructure that disrupts the movement, access and economic activities of residents, who find themselves constantly readjusting and reconfiguring their lives. The military achieves this level of arbitrary control by introducing elastic elements into the landscape: temporary bunkers surrounded by spools of concertina wires; barricades manifesting in various forms such as 'stop and search' posts, armoured bakhtarbands, police vehicles, public buses, steel oil drums or a simple log and stone. These are often accompanied by paramilitary soldiers armed with automatic rifles and shotguns. The choice of element is determined by urgency, highlighting the abruptness of the restrictions (Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society 2017, p. 68). These networks of strongpoints are isolated points which are distributed across the entire territory in an arbitrary way, emerging as a local response, shaping and reshaping the landscape as an autonomous layer hovering above the existing terrain. These small structures emerge as anxious entities born from contested terrain. They are conspicuous not for their appearance, but for the outward display of their potential for mobility, expansion, and transformation. The map highlights the extent of these ‘elastic’ disruptors in Srinagar as of July 2024—‘elastic’ because the system is temporary, mobile and subject to change. The geographies produced by this militarised landscape significantly impact people's mobility and subject them to various forms of surveillance, including constant patrolling, even around residential areas (Mushtaq and Amin 2021).

Systems ranging from: an ordinance to the public institutions in Lahore to increase the height of their walls; the erection of blast-proof walls in Cairo and Baghdad (Shirazi 2013, p. 70); the Israeli wall in the West Bank; the US-Mexico border wall; and the compartmentalisation of space in Beirut—all reflect a pervasive trend of increased militarisation of architecture, underscoring the intensifying efforts to maintain control. In the context of Palestine, Weizman argues that military checkpoints and barricades serve as active sensors within Israel’s surveillance network, enabling brutal segregation (Weizman 2007, p. 7).

Another alteration that disrupts the daily lives of people of Kashmir abruptly is the imposition of curfews, restricting everyone to their homes at set times, while a fear of repercussions looms with ‘shoot-on-sight’ orders in place. Restrictions are imposed on entire cities and towns, not just some neighbourhoods or streets. But when it is localised and intensively targeted, it transforms into what's termed as a 'cordon and search operation', commonly referred to as a 'crackdown,' where a home becomes the battle-site. These operations allow military forces to access private domains covertly, and to enter the private space of individual suspects, similar to ‘straw window’ operations carried out by the IDF (Israeli Defence Forces) in Palestine. Security is placed outside of democratic control.

Transformation

Transformation involves a profound reshaping of the landscape and societal fabric through extensive redevelopment to introduce new infrastructure and systems of control mechanisms that modify the core identity and function of the area.

Srinagar, often referred to as the ‘Venice of the East’, experienced significant urban growth during the late 1950s due to political shifts. This was accompanied by a transition from water-based to road-based transportation. Amidst these developments, the historic Nallah Mar Project serves as a cautionary tale. Originally designed as a waterway to connect Dal Lake and the River Jhelum, it was later transformed into an arterial four-lane road by filling up the canal. While the government maintains that the canal posed significant challenges to urban development, many argue that it was done to facilitate the movement of forces more easily by road than by water, as it reduces the divide between the old and the new parts of the city (Vij 2011). While there are no documents to support this claim, the roadway has met with criticism, particularly for its impact on the city's heritage and environmental sustainability (Irfan 2017).

The French invasion of Algiers in the 1840s by Marshal Thomas-Robert Bugeaud is one of the earliest instances of demolition being used for the purposes of military planning. Bugeaud's extreme actions, aimed at suppressing resistance, included the destruction of entire settlements and the reshaping of cities, to facilitate military movements (Weizman 2003). Similar spatial experimentation and restructuring occurred during British colonisation on the Indian subcontinent and in Palestine—to name a few. In April 2002, the IDF strategically reshaped the entire urban landscape of Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank during what is now known as the Battle of Jenin. The battle initially saw Palestinian fighters holding back an entire army division amidst the dense urban environment. The complexities of urban warfare rendered conventional plans and preparations irrelevant, with the battle unfolding unexpectedly and densely, presenting numerous contradictions. The IDF eventually 'won' the battle by employing bulldozers to collapse buildings on top of defenders, destroying many homes. The IDF reshaped the urban layout of the camp, widening roads and clearing space at its centre to accommodate military vehicles (Weizman 2003). This campaign was a reflection of earlier operations such as the ‘Operation Anchor' in Old Jaffa, executed by British forces, and the counterinsurgency campaign in Gaza by Ariel Sharon in 1971. These are all forms of 'designed' destruction, aimed at increasing the permeability and management of the urban fabric. These methods, including the Bugeaud’s removal of entire settlements to make way for boulevards, demonstrate a recurring pattern of the use of urban design as a tool for control and suppression (Sarfraz and Rafique 2016, p. 103).

Amidst the raging militancy of the 1990s, residential areas in Kashmir faced relentless attacks. The Indian security forces engaged in frequent arson attacks, burning houses, shops and entire neighbourhoods in search of militants. The space becomes a medium for the occupying power. Each action seeks to assert dominance, transform the landscape or appropriate resources, resulting in the creation of ruin and the dispossession of natives from their homes and emotional anchors (Weizman 2007, p. 7). This destruction of property by government forces is perceived by Kashmiris as a form of punishment, reminiscent of the demolitions carried out in Iraq during the occupation and in Palestine by the Israeli state—to name a few (Mushtaq and Amin 2021).

The ‘design by destruction’ approach is not always as overtly violent. In the divided cities of Belfast and Nicosia, conflicting parties and communities are physically separated by a barrier to protect their collective identity. Here, arbitrary urban partitions, reinforced to reduce violent confrontation, completely transformed the regions into permanent urban minefields navigated daily by residents who are unable to avoid them. Cities are typically divided by external forces aiming to protect, save or claim them without considering the residents. Boundaries evolve into barriers, and these barriers then dictate behaviour (Calame and Charlesworth 2009, pp. 1–8). This ‘politics of separation’ is exemplified by the construction of the apartheid wall in 2002 by the Ariel Sharon administration. While the 1949 armistice line theoretically divides the city into West (Israeli) and East (Palestinian) parts, true urban separation arises from this wall, violently dividing Palestinian neighbourhoods.

The construction of the Jammu-Baramulla railway line, which commenced in 2002 and was intended to connect New Delhi with Baramulla in Kashmir, is an example of one out of many national highway and road construction projects, where Kashmiris lost their orchards and fields in the name of development. Trains have historically been linked with colonial aspirations in India. The first railway line in the subcontinent was opened by the British in 1853, facilitating the export of goods to Europe, and providing significant political advantages by enhancing military mobility. Half a century later, Kashmir faced a similar strategic challenge during the 1999 conflict between India and Pakistan. With inadequate road infrastructure in the mountainous region, India struggled to supply troops during the Kargil War. This led to the initiation of a railway infrastructure project, allegedly aimed at fostering development in Kashmir. The true motivation however, was to address the logistical shortcomings exposed during the conflict (Crowell 2018). The project has also exacerbated the region's vulnerability to natural disasters. During the devastating floods of 2014, the high railway embankments contributed to the destruction of villages and farmlands, underscoring the disregard for local concerns, in the pursuit of national interests (Mushtaq and Amin 2021). Thus, while the railway project symbolises India's efforts to consolidate its control over Kashmir, it also highlights the tensions between development, security and the well-being of local communities.

The mapping of these projects indicates the presence of various mobility initiatives that have fundamentally transformed the landscape of Kashmir and resulted in the dispossession of land for many residents. The prioritisation of military mobility over civilian transportation underscores the complex dynamics of infrastructure development in conflict zones. Convoy movements frequently disrupt civilian traffic, reflecting the state's use of waiting as a mechanism of control. This militarised approach to infrastructure further exacerbates tensions and impedes the region's socio-economic development.

The restructuring of urban fabric for military purposes is not uncommon, as demonstrated by these historical examples. Military control is exercised through strategic urban design, with cities being adapted to facilitate military operations. This approach has been employed both at the periphery of Western civilisation, and in city centres, albeit often camouflaged under different rhetoric. The upgrade of infrastructure and living standards may seek to eradicate the conditions that breed discontent, but also, increasingly, to generate vulnerabilities that may reduce the motivation of the urban population to support active resistance (Weizman 2006).

Construction

In occupied territories, construction manifests in the restructuring of cities in ways that can be delineated as: the reappropriation of land for military use; the reorganisation of inhabitants; and settler colonisation. These classifications are utilised either independently or in conjunction, outlining multifaceted approaches to urban restructuring. The process of construction fundamentally shapes the physical and functional landscape, embedding control and governance into the very fabric of the environment.

Reappropriation for Military Use

The term ‘infrastructure’ was officially adopted by NATO (2001) in 1949, encompassing all fixed installations facilitating military operations. Over time, this term has been misappropriated to infringe upon the democratic use of space and the rights of people. When Indian forces first arrived in Srinagar, they seized control of the Srinagar airfield. This strategic gateway into the Valley was initially constructed by the military for defence purposes, but is now used as a civilian airport as well. Following the 1962 Sino-Indian war, another airfield was established in Awantipora, which serves as a satellite airfield for Srinagar. In 2020, the construction of an emergency three-kilometre-long runway parallel to a segment of the Srinagar-Jammu National Highway was initiated. While clarifying that the project was unrelated to the stand-off, a senior Army official emphasised its strategic significance, noting that future highways could serve as invaluable assets for the Air Force. Following this, certain public roads have been designed to double as runways in the event that key airfields are compromised by enemy attacks (Majid and DHNS 2020). The military also constructed camps which are scattered across the Valley, often within a 5-mile radius. They are easily recognisable by their expansive compounds, rectangular buildings with olive green roofs and camouflage-painted armoured personnel carriers, which are always ready to transport troops for operations. The areas near the Line of Control of Operation Sadbhavana are effectively under military rule, with strict movement regulations. These vast zones, where daily life is dominated by military authority, often go unnoticed (Mushtaq and Amin 2021). The examples described here illustrate the broader pattern of military land occupation in Kashmir. The military is also involved in the establishment of schools; women’s empowerment centres; sports activities; infrastructure projects such as water supply schemes, road connectivity and electrification initiatives; medical aid centres; and model villages under Operation Sadbhavana. These projects are intended to alleviate alienation and improve the social indicators of the military. The presence of such a large number of armed infrastructures has significantly influenced land-use patterns in Kashmir. Every topographical feature of Kashmir's varied ecosystem, including highlands, glaciers, forests, mountains, hills, paddy fields, stream beds and lakes, has been subjected to the environmentally destructive consequences of military manoeuvres, encampments and permanent military establishments (Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society 2015, p. 37). Recent modification to the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Development Act and the Building Operations Act, now allows any region in J&K to be designated as a ‘strategic area’ by the military forces (Kanjwal 2020). Critics fear that the amendments could lead to the militarisation of the entire region and the seizure of prime land, disregarding existing laws and property rights.

In Palestine, Israeli settlements were initially established as military outposts, purportedly for security reasons. Settlers later transformed these into a civilian homeland, exploiting the international law that permits the construction of military infrastructure as the sole justifiable Israeli development in Palestinian territories. Bunkers and outposts constructed on occupied territory under the guise of security are, in reality, tools of oppression, utilised to dispossess the indigenous population of their land (Allweil 2016, p. 23). American bases located in remote areas worldwide, similarly capitalise on the concept of infrastructure. These bases are meticulously planned with a limited resident population of military personnel, often encroaching upon the lands of locals. Externally, these bases present themselves as heavily fortified gated enclaves, ostensibly safeguarding the elite while perpetuating segregation and exclusion (Gillem 2005, p. 11).

Reorganisation of Inhabitants

While the Master Plan 2035 obscures the military occupation, it simultaneously aims to expand Srinagar's metropolitan area and create new residential and investment zones. The Master Plan envisions division of the area into 53 zones, which include high-density developments and special investment corridors, raising questions about the intended beneficiaries. Kashmiri residents fear an influx of outsiders following the abrogation of Article 370, leading to potential changes in land ownership and demographics. The plan introduces new actors and changes to land ownership laws, potentially marginalising vulnerable populations (Das 2020).

This zoning and grading strategy has historical roots in the reorganisation of rural and urban populations in Algeria during French Occupation. The French authorities’ forced resettlement of around three million people through the ‘regroupement des populations’ and the creation of regrouping centres referred to as resembling camps, which were strictly overlooked by specialised army units known as the Specialised Administrative Sections (SAS). The centres, though appearing as planned rural settlements, served military surveillance and enforcement purposes (Henni 2016, p. 41). These measures led to the displacement of millions, and a lasting socio-economic imbalance, undermining structures resistant to colonialism. In Egypt’s Madinet Nasr, a government-sponsored desert expansion uniquely involves direct military participation, with military infrastructure dotting the landscape. This exemplifies the fusion of military and urban development (Elshahed 2015, p. 24).

Settler Colonialism

Historically, India exerted control over Kashmir through military occupation and a puppet legislature. Post-2019, this control has extended to the bureaucracy, marking a significant shift towards settler colonialism. The settler collective in Kashmir aims to transform itself into a native polity (Veracini 2022).

This trajectory starkly parallels the beginnings of settler colonialism, drawing comparisons to the Palestinian case. In Palestine, the Israeli military’s urban planning strategies extend into civilian occupation, where the presence of civilian architecture is leveraged to demonstrate Israeli dominance across the landscape (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003, p. 22). The transformation of settlers' housing ethos, from shelter to political tool, began in the 1990s in response to negotiations over a two-state solution. Initially portrayed as temporary military outposts, settlements evolved into permanent civilian communities. The mere presence of these buildings becomes a tool for achieving an effect of dominance, as seen in new settlement developments aligned with the Allon Plan. These settlements, comprising just 2% of construction, create new geographies as wedges, achieving complete fragmentation and control of the West Bank. Their locations, dictated by hilltops to exercise power through vision and height, are strategically woven together by highways that are for the exclusive use of settlers (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003, p. 109).

If civilians from the occupying power substantially contribute to the security in an occupied territory, and facilitate the execution of military strategies, it becomes clear that armed resistance elements operate more easily in areas where the population is indifferent or hostile, rather than in areas where residents are likely to observe and report suspicious activities to authorities (Segal, Weizman and Tartakover 2003, p. 86). This phenomenon of militarised civilian architecture reverberates beyond the immediate region, finding parallels in global landscapes of conflict. It highlights the broader implications of using architecture as a tool for geopolitical domination and control.

The Inflicted Space

Military occupation in Kashmir manifests not merely in the presence of soldiers but as a deliberate and layered spatial strategy; space is no longer a background for the actions of occupiers, but has evolved into an apparatus of warfare. This is enacted through techniques of adaptation, alteration, transformation and construction which do not operate in isolation, but overlap and interact across multiple scales. From the intimate, private space of the home, to a city-wide redevelopment; from arbitrary curfews to perpetual land seizures, everyday spaces in Kashmir are reconfigured into a frontier zone—temporary, contingent and never complete.

The military is embedded within the civilian infrastructure, making and unmaking spaces, and re-engineering them to enable seamless movement across occupation infrastructures. This extensive and intrusive infrastructure regulates mobility, assembly, sociality and everyday life, producing an oppressive environment that strips Kashmiris of their right to the city. The apparatuses and institutions claiming to ensure security, paradoxically, jeopardise the well-being of the residents.

Within the spatiality of occupation, the elements of architecture and urban systems lose their traditional conceptual simplicity and material fixity, rendering them, on different scales and occasions, as flexible entities, responsive to changing political and security environments.

By situating Kashmir within the broader global condition, the present analysis not only enhances our understanding of Kashmir’s unique realities but also draws attention to the spatial logics of power and the way scholars think about the built environments. It amplifies marginalised perspectives, producing a body of knowledge that challenges conventional state narratives.