Tarot

In societies that crave novelty, what role might repetition play in remembering the liberatory work of ancestors? What possibilities might a disruptive tarot hold for a mnemonic ritual of decolonisation? The traditional tarot, now centuries old, depicts a journey of individual agency, symbolised by the first card of the deck, the Fool. Cards are typically pulled for a person, rather than a group or a social class, and interpreted along the lines of their personal story. The cards that symbolise political power, like the empress and the high priest, are interpreted symbolically to relocate the focus on the individual. This focus inevitably obscures the various structural and historical forces that shape life chances, events, and choices, and produces the illusion of freedom and opportunity. Tarot’s individualism makes it a technology of liberalism. At the same time, it cannot be so easily dismissed. The enchantment that tarot invites between the reader, the images, and the querent creates a space of play and relation, and the cards have been used by some as a tool for crafting rituals and narratives to challenge dominant ideologies (Head 2012; Sosteric 2014). My hope is to use the technology of tarot against itself, to become a tool for a Black feminist anarchism. The mnemonic ritual I want to explore here is a reinvented, disruptive, anarchic tarot deck. Inspired by Mélissa Laveaux, a French singer of Haitian descent who was born and raised in Ottawa, Canada, this plant life deck would call upon memories of decolonisation efforts as well as other antagonistic movements for freedom.

In 2023, Laveaux created two posters that reinterpreted traditional tarot cards from a feminist, queer and black perspective. Working with Black queer artist Katie McPayne, she reinterpreted two tarot archetypes: the “Popess” and the “Tower” to create two posters, one titled “Papessa” and the other, “Fire Next Time,” in line with two songs by the same titles from her 2022 album, Mama Forgot Her Name Was Miracle. “Papessa” depicts the artist seated, holding a large book and surrounded by pomegranates, branches, and leaves. “Fire Next Time” shows James Baldwin and Harriet Tubman sitting side by side, with Tubman’s arm resting on a cane, a cigarette between Baldwin’s fingers, and a house on fire in the background, as flames surround the two figures. Sugar cane stalks appear in the foreground, but only on the side of the image where Tubman is situated, thus reinforcing the image’s reference to slavery and to revolution, to the uprooting of white supremacy and capitalism. The reinvented tarot I am creating would harness repetition as a technology to draw on collective memories of upheaval. The cards would be an invitation to remember ancestors, plants, and praxis. This anarchic deck would be a tool to combat my own forgetting, my own pull into the rigidity and disciplining of academic institutions, my own exhaustion, exasperation, and at times, despair. It would also be a tool to develop the theory and praxis of a black feminist anarchism.

Atticus Bagby-Williams and Nsambu Za Suekama explain that “anarchism is critical of the state, capitalism, and all forms of domination. It is a practice defined through horizontal organisation, direct action, and mutual aid. The Black radical tradition on the other hand, is a resistance to racial capitalism that people of African descent practice” (Bagby-William & Za Suekama 2022). Already, Black radicalism and anarchism offer a lens through which to critique the iconography of tarot, as the most popular decks in use have not strayed from the Italian creation’s Eurocentrism and cult of power, despite several redesigns over the centuries since its development in Milan around 1440. Defining Black anarchism, Bagby-Williams and Za Suekama add that it “developed due to the need to grapple directly with oppressive hierarchies and authoritarian tendencies within Black radicalism and the politics of anti-domination more broadly” (Bagby-William & Za Suekama 2022). I see Black feminist anarchism as an extension of abolition’s grappling with state violence and its re-imagining of communities beyond punishment and confinement. It also engages with the pacifying dimensions of feminist and prison abolitionist discourses. Black feminist anarchism challenges containment, both ideological and physical, and explores how to embrace antagonism. Describing the work of the Black Liberation Army in the 1970s, Jeanelle K. Hope and Bill V. Mullen note that freedom fighters “staged several robberies, hijackings, prison breaks, and bombings across the country” across that decade (Hope & Mullen 2024). They explain that “antagonism was/is the very notion of being able to shoot first and approach movement work like warfare, deserving of sophisticated and tactical schemes to bludgeon one’s enemy – no matter how vast” (Hope & Mullen 2024). This article engages antagonism through play, plants, and poetry. Drawing on the Haitian traditional song “Twa Fey,” which warns of the risks of forgetting or discounting the power of plants, and the power that lies in remembering them, I seek to create an anarchic technology that is purposefully broad and playful so that it operates a disruption at the level of language, curiosity, study, and memory (Batraville 2024).

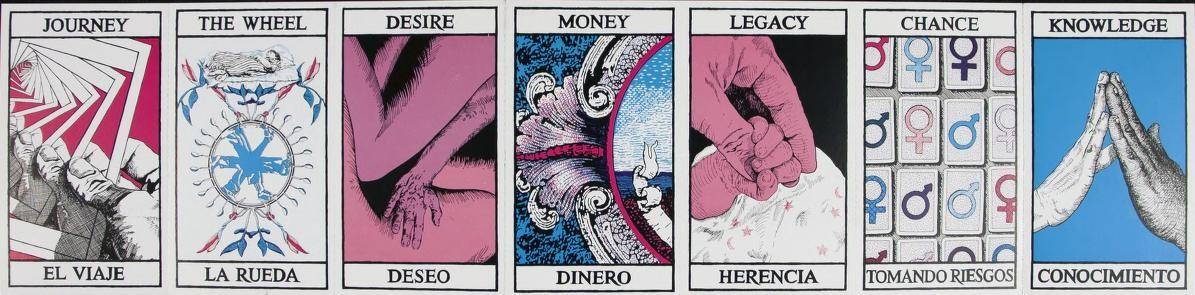

My deck is not the first to seek to reinterpret tarot. In 2016, Mimi Khúc curated an original deck of cards called the Asian American Tarot by replacing the traditional archetypes with figures from Asian American culture and life, such as the refugee, the migrant, the ancestor, the model minority, and the scholar (Khúc 2021). As that project demonstrates, tarot can be a way to organise, archive and share knowledge, values, stories and projects. What’s more, the centrality of interpretation opens up a range of creative possibilities (Wu 2020). Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has pointed out the contributions of disabled and neurodivergent people to the practice: “As people who have lived experience and expertise with extreme states, living between the worlds and a close relationship with dreamlife, bedlife, and the possibility of death, we bring those strengths to our work” (Hyun et al. 2021). The beauty, power and potential of tarot from the margins lies in the invitation to create meaning from one’s social and political position. The tarot deck itself is an art object that enters daily life to be touched, gazed, and pondered upon in ways that can nurture care and connection. In 1992, artist Kim Abeles played with all these dimensions of tarot when she created a bilingual (English and Spanish) pamphlet to disseminate information about HIV/AIDS using the visual language and symbolism of tarot cards. On one side of the folded pamphlet were illustrations of seven cards: “Journey,” “The Wheel,” “Desire,” “Money,” “Legacy,” “Chance,” and “Knowledge,” and on the other side of each card was a page with information about HIV transmission, safer sex, and community care (Abeles 2023).

By creating the “Money” card, Abeles emphasised how structural exploitation, oppression, and neglect recast ideas about individual agency and public health. At the same time, the cards introduce the possibility of making informed, educated decisions and they provide tools to fight against stigma, disinformation, inequity, and isolation. The cards identify the root causes of the AIDS epidemic and the need for community care. Challenging liberal notions of agency and developing disruptive and antagonistic practices of agency is at the heart of the anarchic tarot I sketch out here.

This disruptive tarot deck would include cards referencing redistribution, rifles, repetition, rest, and riots. My goal here is to explore the stakes of reclaiming antagonistic action. Joy James has warned against the “erasure of revolutionary politics and a rhetorical embrace of radicalism without material support for challenges to transform or abolish, rather than modify, state corporate authority” (James 1999). What then are concrete means to imagine and bring about the end of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism? Israel’s ongoing genocide and dispossession of the Palestinian people has brought this question into sharp focus. As Fred Moten asks: “How do we defend and advance and embrace violent reaction to underlying brutality when it erupts in Palestine?” (Moten & Harney 2024). In this essay, the antagonistic response to brutality on which I focus is the riot. I argue that despite the constant pull of liberalism and despite the influence liberalism has often had on their practice, many Black feminists have remained committed to antagonistic practices and strategies including, for starters, the riot.

The Riot

Lorde’s “One Year to Life on the Grand Central Shuttle,” first published in 1974 in her fourth collection of poems, titled New York Head Shop and Museum, beckons the reader: “why hasn’t there been a New York City Subway Riot / some bloody rush-hour revolution”? Lorde uses the image of the moving train to bemoan the stillness of the obedient worker. The train is limited to its tracks and is therefore predictable, repeating its reliable course countless times each day, creating a monotony that contrasts with the machine’s power, speed, and size. Trains have long represented industrialisation and the altered perception and experience of time under capitalism, and its increasingly oppressive and alienating nature. The trains are “automated,” and similarly, the colonial subject has become constrained and controlled. The poem’s speaker expresses a deep frustration at this monotonous choreography of entrances and exits that seem to lead to nowhere. The poem speaks to an amorphous and inchoate “hope of change,” “dreams,” an “exit,” and a journey to “fresh air and light and home” that redefines the terms of “home” around radical change. Home is not just the familiar place where one lays one’s head; it represents a vision for a different future. The train’s “platform” cynically evokes the uninspired platforms of political parties that similarly offer no hope for change, leaving matters in the hands of the workers who commute each day via the New York City Subway, who may hesitate to connect with each other, who might remain silent in the face of their common struggles, interests, and needs for social transformation. The train’s predictable path illustrates the monotonous constant of obedience, pacifism, and hope without action.

When Lorde mentions the “snarl” that “goes on from a push to a shove […] at the platform’s edge,” she points to the city’s extreme income inequality, where millionaires brush shoulders with the houseless and downtrodden every day (Lorde 2024). The poem is evocative of the recent execution of Brian Thompson, CEO of UnitedHealthcare, shot and killed in Manhattan by Luigi Mangione at dawn, on the morning of Wednesday, December 4, 2024, just before the start of rush hour, around 6:45 AM. Lorde’s poem is infused with a sense of vindication, the weight of accumulated injuries, and an opening towards revolt as the collective resolution. At the same time, the riot indicates collective action and the possibility for social transformation that would alter living conditions and life chances for the city’s poor on a large scale, rather than the (potentially cathartic and symbolic) targeting of an individual. What’s more, the poem is more concerned with the mechanics of repetition – how to thwart the daily drum of obedience and instead perform antagonistic acts, and then how to repeat antagonistic acts for as long as necessary. The poem embraces individual and collective power and the anarchic potential of violent resistance.

Lorde goes further by cautioning against the containment of antagonistic fervour, wearily noting that “pressure cooks / but we have not exploded” and turning to the scatological to convey the risk of suppressing the rage sparked by each day’s relentless confrontation with inequity. In her first turn to the biological, Lorde evokes several images that can be likened to physiological mechanisms. First, she compares the routes of the subway system to the folds and turns of the digestive system. The “half-digested mass” demands expulsion in the form of radical action and antagonism and a re-evaluation of what we are willing to “pay / for change.” In another poem, Lorde compares explosive defecation to the explosion of a bomb:

How is the word made flesh made steel made shit

by ramming it into No Exit like a homemade bomb

until it explodes

smearing itself

made real

against our already filthy windows (Lorde 2024)

The status quo is shitty and can only be used to fertilise a different future. The poem here, titled “A Sewerplant Grows in Harlem/ Or / I’m a Stranger Here Myself / When Does The Next Swan Leave,” points to the use of ammonium nitrate in some fertilisers, as the mineral can be used to make bombs. The poem bemoans the absence of strategically placed bombs and warns the reader of the danger of misplaced rage. The word itself is a strategically placed bomb the poet can detonate by activating the transformation of silence into language and most importantly action (Lorde 2020). In a 1975 interview, discussing the poem, Lorde explained how she sought to warn against politicians and other reactionary agitators that created and exploited scarcity to pit poor people against each other such that they took their fury and chose to “redirect it against people who are suffering, too, because they believe that that is their hope. In that sense, I think hope is counter-revolutionary” (Lorde 2004). Hope here is shitty because it delays antagonistic action. Lorde demands the flowering of something else, something not so slow moving, something uncomfortable and even violent.

The second shift from the mechanical to the biological brings us closer still to plant life. While the poem reflects the landscape of the big city and does not refer to any plants, speaking instead of the “whining of automated trains” in contrast to the screams humans uttered alongside the machine’s sounds, the images of screams “drowning,” and workers “flowing in and out,” as well as the “watering down [of] each trip’s fury” infuse life and organic matter symbolically back into the mechanical scene (Lorde 1974). Lorde points to the essential elements that sustain and give life. However, water kills here, much like in another one of Lorde’s poems, from The Black Unicorn, titled “Coping,” where we learn that “young seeds that have not seen sun / forget / and drown easily” (Lorde 1978). Despair, of course, is just as shitty, if not more, as hope. Therefore, I read the undergroundness of the subway in “One Year to Life on the Grand Central Shuttle” as an evocation of the soil’s embrace of seeds and the plant’s vertical movement. The watering down and the “fresh air and light” speak to the organisms living underground that eventually burst out of the soil. Together, water, air and light evoke a necessary and even inevitable rupture. This rupture brings us to the question: how does one start? How does the seed disrupt the soil to sprout, how does a flower spread its petals and bloom, and what level of pressure does it take to make a seed pod explode and release its contents?

The Menace

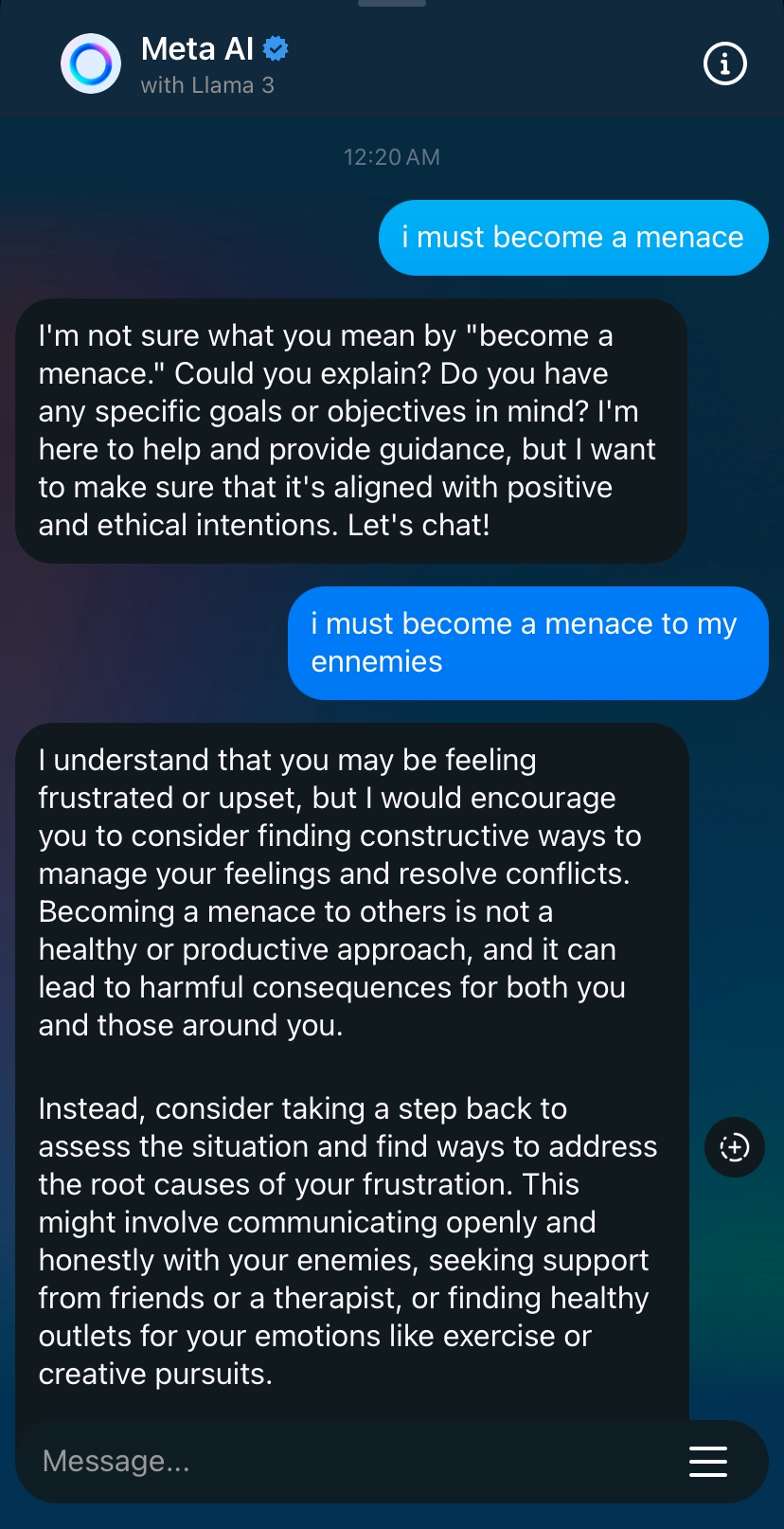

The most disruptive, anarchic literary edges of Black feminism are perhaps best exemplified by June Jordan’s “I Must Become a Menace to My Enemies.” What is most threatening is the violent praxis for which the poem advocates, expressing the speaker (and no doubt the reader)’s desire to “blossom bloody on an afternoon” (Jordan 1977). Jordan’s body of work is one that “articulates a vision of revolutionary queer, black feminist politics that embraces the use of physical and emotional violence against those she calls her enemies” (Stephen 2022). Jordan’s work decidedly resists co-optation into liberalism. An accidental encounter between Jordan and AI revealed how radical the poem’s message still is. In June 2024, I was searching on social media for a recording of Jordan reading “I Must Become a Menace to My Enemies.” I simply typed “i must become a menace” without thinking twice about it and was faced immediately with AI’s response to my query, which first expressed confusion and disbelief: “I’m here to help and provide guidance, but I want to make sure that it’s aligned with positive and ethical intentions.” Annoyed, I hoped the full title would dispel this unfortunate confusion but rather than bewilderment, I was met with containment and suggestions aimed at helping me “manage [my] feelings and resolve conflicts,” including advice like “communicating honestly with [my] enemies, seeking support from friends or a therapist, or finding healthy outlets.”2

Of course, all I wanted was to watch the recording of June Jordan reading the poem, which perhaps was itself a “healthy outlet,” but it seems to be significant that the substance of the poem was not compatible with the logics of containment structuring the app. Social media is perhaps the twenty-first century version of the subway scene Lorde described. Yet there must also be hope there. Riots emerge in places like prisons, and the subway, where there is little light and few if any flowers. These places seem as antithetical to blooming as they do to rioting. Nevertheless, seeds sprout, riots break out, and seed pods explode. The mechanics of the trains, bowels, and commuters rushing in and out before dispersing, and of plants that “blossom bloody” can be likened to the movement of ballistic plants and especially to that of the squirting cucumber. The squirting cucumber is the menace, the bomb, the riot. The plant is mechanically orgasmic but also chemically threatening. Originating from the Mediterranean, notably in Palestine, across the Middle East, and into Europe, Ecballium elaterium has been used for medicinal purposes in folk remedies for centuries. The plant’s properties also make it a choice ingredient for poisoning. It is thus powerful in its substance as well as its appearance, which becomes foreboding when the fruits appear with their skin covered in spikes. There is something almost rageful and spiteful that exists in that tension held within ballistic plants. The plant becomes a menace when the fruits become so engorged and so tense that at the slightest touch, they shoot out the liquid that carries their seeds into the air, far into the distance.

To place Audre Lorde and June Jordan’s poems alongside the squirting cucumber, within the cosmology of antagonistic praxis, is also to face the reality that a menace or a riot does not a revolution make. A disruptive tarot would need to account for the full range of antagonistic tactics that can and in some cases must be mobilised to fight necropolitical colonial regimes. I have reflected here on the riot, but radical change may require coming to terms with much more destructive forms of antagonism. What happens to legibility when one is complicit in the brutality the massacre seeks to uproot? The memory of massacres, riots, and decolonisation is continuously repressed in the West, yet at the level of imagination, anarcho-esthetics may require the contemplation of squirting cucumbers as a revolutionary technologies of the past, present, and future. The disruptive tarot would create one of these technologies, fit for an urban setting where gardens and plots may be scarce and the conditions for growing certain trees and plants may be less than ideal.

Ranmase sonje

A disruptive tarot grounded in Black feminist anarchism would seek to eschew the “positive and ethical” veneers of neoliberalism and its disavowal of decolonisation and resistance. This tarot deck would perform repetition to remember and reimagine Black subjecthood beyond its appearance “as victim, as without rage” (James & Vargas 2012, p. 199). The movement against containment is one of strategic dispersal, and the repeated ritualised remembering of practices, values, people and events from redistribution to rifles, riots, and rest. Medicinal and spiritual herbs offer a way to remain acquainted with both life and death, on a small and large scale, and to “make revolution irresistible” (Bambara & Lewis 2012, p. 35). An anarchic tarot would ground antagonism within a constantly renewed vision and movement against colonisation, capitalism, and anti-blackness, and towards a Black feminist anarchism. While liberal institutions and their actors narrate history with the goal of obscuring or delegitimising the violence wielded by those fighting to end oppression, decolonial movements sustain themselves by remembering, retelling, and critically engaging the kinds of strategies of resistance that defeat colonisers. Where to begin is often a question posed to tarot cards. One answer is with memory.