The Nocturnal Proclamation: Night as Method and Insurgency

Your shadow stretches out behind you as you step into the blinding day. There is piss in the alleyway, still warm, the ammonia rising. On the pavement, a takkie lies abandoned, laces undone — an unspoken narrative of escape, of loss, of what transpired in the folds of darkness. The night, you think, does not erase itself; it inscribes. It writes in fragments, in stains, in remnants. Even the most meticulous cleanup crews cannot undo what the night has etched into the city’s architecture. The night never ends, it only recedes. Its residue can be felt in the gaps of the city, in the half-light of morning. It clings to the pavements — cigarette stompies, smashed beer bottles, the damp remnants of a body passed out on the curb. It stains the walls in graffiti scrawled under the cover of darkness — thick defiant lines, letters dripping into dawn. The night exceeds itself. It is not confined to the hours of its rule but lingers, bleeds into the day.

Night is no metaphor, no mere backdrop. It is praxis. Its revolutionary possibility has long been recognised by those who seek to challenge ideals of enlightenment. The sleep of reason that produces the kind of monsters so feared by Hegel was something that the surrealists hoped to induce by excavating, interpreting, and applying a space of dreams, delirium, subversion and unreason, a counter-temporality.

Georges Bataille, one of surrealism’s most radical figures, extended this nocturnal turn through Acéphale (‘headless’), a Paris-based journal and secret society that ran four issues between 1936 and 1939 (Monoskop 2022). Together with André Masson — who illustrated the journal — and five others1, Bataille formed a “Sacred Conspiracy” that met clandestinely in moonlit forests beneath an oak tree split by lightning. These nocturnal rituals included readings from philosophers Marquis de Sade, Friedrich Nietzsche, and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud — texts that, like the night, opened pathways into transgression, ecstasy, and excess (Bataille 1988; Hollier 1989); often in direct contrast to the contemporary fascist interpretations of their work (Bataille et al. 1937).

The fascination with night as a realm of unreason resonates across older traditions globally. In Iran, classical musicians still only play certain dastgāhs (modal systems) between midnight and 4 a.m., inheriting ancient mourning rituals tied to burial rites (Mohaghegh 2022, p. 52). In Japan, the storytelling tradition of kaidan (ghost tales) is similarly bound to the hours after midnight, when spirits are believed to roam free. In different parts of Africa, night is often a sacred interval of transformation (Hearn 1968, pp.6-14). The Dogon people of Mali perform celestial rituals under the stars, mapping cosmology through masked dances and chants. In the Xhosa ulwaluko initiation tradition, night marks a passage through shadow, silence, and pain into adult identity — an embodied, communal reckoning with the unknown. Across these cultural lineages, night is not merely an absence — a break or pause between one day and the next — but a generative force: birthing new forms of consciousness, language, and art (Slasha 2017, pp. 34-88).

Under apartheid South Africa, the night became a politically charged terrain, both forbidden by law and fiercely claimed in resistance. From roughly 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., Black South Africans were barred from urban centres, a system tied to pass laws that rendered nocturnal movement a crime (Goldberg-Hiller 2023, p. 98–133). As the state sought to render the night inert, the township pulsed with clandestine life: shebeens — informal, often woman-run taverns — emerged as spaces of resistance, hosting gatherings where jazz, marabi, and kwela music became sonic forms of defiance (Coplan 2008, p. 224-340). In Sophiatown and Soweto, these venues sheltered secret political meetings, performances, and communal dreaming (Hirson 1979). The curfew was implemented to discipline and silence; instead, it produced a nocturnal insurgency where culture, politics, and community would thrive (Briers 2024).

Today, these insurgent possibilities are complicated and imperilled by rising crime, deteriorating infrastructure, the hoarding of resources, and, at the heart of it all, the relentless expansion of capitalism (Comaroff and Comaroff 2006; Bremner 2010). The gated enclave stratifies the night, illuminating small pockets for the few, and creating danger zones for the many (Falkof and van Staden 2020). In townships and inner cities, the streetlights fail and transport halts early, curtailing movement and gathering once more. And yet, the night’s revolutionary pulse endures in underground scenes that reimagine the possible beneath the cover of dark.

That was how we found them. It was 2023, in the thick of the energy crisis, the city reeling from Stage 6 load-shedding. We were in Joburg to collaborate on another project that never saw the light of day. We first noticed the traces near the burned-out payphone on Nugget Street — a series of torn images wheat-pasted onto the corrugated metal of a shuttered spaza shop. Distorted, overexposed photocopies: a feverish etching of tangled bodies and skeletal dwellings, where figures crouch, climb, and toil, as if caught in the middle of some unfinished exodus; a sequence of grainy black-and-white photographs that capture a solitary figure interacting with a chalk-drawn payphone, their gestures shifting from curiosity to desperation, as if attempting to call out to something — or someone — long disconnected. Below the images was a scrawled line of text in thick black ink: “Imbewu Y’Ubumnyama”. The words sat uneasily on the surface, smudged, as though deliberately blurred.

That night, as the city plunged into darkness, another round of load-shedding swallowed the last remnants of neon. On such nights, erasure is not just a textual strategy but a material condition. Load-shedding in Johannesburg is more than infrastructural failure; it is a rupture in visibility, a forced entry into a different mode of seeing. We sat in the all-night KFC (one of the few places in Braam with a generator), and, under the glare of the overhead lights, flipped through some photographs — now long gone — that we had snapped with our phones. We paused on a series of photocopies pasted on a wall. Isn’t this Feni? Koloane? The more we looked, the more we saw connections — the way the graffiti along Rissik Street mirrored the scrawled phrases we had seen, the way certain symbols appeared and reappeared, altered but persistent. Could this be a movement — necessarily shadowy, unstated, fugitive?

To write about Imbewu Y’Ubumnyama requires us to confront the paradox of articulation itself — to acknowledge that the moment of exposure is also the moment of distortion, the moment of betrayal. What right did we have — two white writers — to shine a light on their work? That said, Imbewu Y’Ubumnyama insists on articulation, not in spite of this paradox, but because of it. In his essay, “Metamorphic Thought: The Works of Frantz Fanon” (2012), Achille Mbembe engages Fanon’s capacity to speak with luminous clarity while dwelling in the nocturnal world; the world of poetic and revolutionary ferment.

Fanon vehemently opposes Manichean logic, which divides the world into binaries of good/light/pure versus evil/dark/impure. This binary, inherited from the ancient religion of Manichaeism, becomes, in Fanon’s usage, a metaphor for the racialised and paranoid moral schema of colonialism.

His thought is dialectical and dynamic, grounded in the belief that humanity is always in motion, always becoming. This suggests a politics that rejects the fantasy of pure visibility and stable classification. Instead, it proceeds by tracking movements, coordinating transformations, and organising transversal solidarities.

A parallel exists in the writing of the academic Carli Coetzee, who, in expressing her “reluctance to accept an easy ‘post’ position for South Africa […],” is also unable to adopt the view that “nothing has changed, that the ‘post-ness’ is somehow fake” (2013, p. ix). Both, she writes, rely on the binary logic of day and night, black and white — the ‘expectation that the end will be finite, that there will have been a morning when the world woke up to a new day that bore the traces of what had gone before” (2013, p. ix). Instead, she argues for an approach to the ‘long ending’ of apartheid as an ‘activity’ (2013, p. x); one that requires constant work but that is also aware of the power imbalances at play in any given context, and the possibility that one’s speech therein — or by extension, the things one puts into the world — risks ‘being absorbed into another speech with another set of codes and desires, those of the text quoting and containing the reported speech” (2013, p. 21). The fact that one may “not want every reader or listener to ‘understand’ […]” (2013, .p 21) does not mean one should not speak or be seen. Rather, Coetzee, like Fanon, does not seek to anchor the subject or object but to facilitate its freedom and movement.

In this tradition, Imbewu Y’Ubumnyama evades easy representation but still demands presence. While their work may not be explicable, it still insists on being felt. Jazz musician Johnny Dyani (2010, p. 23) captures this. His thinking resonates with the idea that some knowledge, some artistic expressions, should remain unreadable, or at least resistant to the structures that seek to codify and claim them.

Édouard Glissant's concept of opacity picks up Fanon’s charge, challenging the colonial desire for transparency, legibility, and mastery. Against the Western imperative to know, explain, and define the Other, Glissant proposes opacity as an ethical stance — a refusal to reduce the irreducible, to violate the interiority of the unknowable. “We demand the right to opacity,” he writes in Poetics of Relation (1997), not as a retreat into obscurity, but as an affirmation of difference without hierarchy. In the context of artistic and intellectual expression, opacity is resistance; a way of withholding, protecting, or preserving the sacred.

Dyani’s anecdote — that to name the chord is to betray it — echoes this critique. The question is not whether one can understand, but whether one is prepared (spiritually, emotionally, somatically) to engage. This is what we might call relational readiness.

Toward a Shadow Archive

In Archive Fever (2002), curator, critic and poet Okwui Enwezor interrogates the archive as both an apparatus of control and a site of contestation. The museum, even when it gestures toward inclusion, remains bound to the logic of visibility — it catalogues, exhibits, makes legible. It presumes that to preserve is to reveal. But this logic is not without remainder. There is always something that exceeds the archive: a residue, a murmur, a dissonance that cannot be indexed.

This excess is not merely metaphorical. The fascination with “the museum at night” — from after-hours exhibitions to nocturnal programming, popularised by the 2006 film, Night at the Museum — reveals an institutional intuition that something shifts when the lights go off. At night, spatial and epistemic hierarchies loosen. Objects become silhouettes; didactic panels recede; interpretation stutters. Curation no longer clarifies — it disorients. What the night reveals is not the object itself, but the instability of its framing.

Enwezor (2002, p. 21–23) describes how photography, as a documentary practice, oscillates between revealing and concealing. The archival impulse is always haunted by what it cannot capture. What if we took this tension as method? If the archive is a tomb, as Mbembe (2002: 19–26) writes (after Enwezor, Derrida, and Foucault), a sanctified vault where debris is interred — consecrated by law and order — then what happens when the night intervenes? Not to just mourn, but to reanimate? In many African cosmologies, night is not a lull but a breach: the hour when the dead rise, when silence is torn open by ancestral murmur and spectral noise. The night (vigil) is not, to reference the filmmaker Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese (2019), a burial but a resurrection.

Mbembe calls the archive a place of “co-ownership of dead time” (2002, p. 19–26), a zone of sanctioned memory and sealed secrecy. But what of those who refuse to stay buried? In his makeshift archive, The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember (2021–ongoing), artist Kudzanai Chiurai assembles an insurgent memory bank — vinyls, pamphlets, images, objects that refuse the neat containment of nationalist myth-making. His library is haunted by what was edited out: Black Consciousness radio broadcasts, political ephemera, protest posters that survived by becoming illegible. Here, the archive is not a mausoleum but a haunted speakeasy — an off-the-record memory gathered in resistance.

It wasn’t long after that the writer and scholar Tinashe Mushakavanhu (2020) went digging in the National Archives of Zimbabwe that things started to go missing. “When I told friends about the appearance, disappearance and reappearance of materials,” he writes, “many suggested that the institution has a general suspicion of researchers and that it censors information.” In place of Dambudzo Marechera’s papers, he found a pile of letters, written posthumously to the author. “The melodramatic structure and rhetoric of the letters disturbed the stable meanings I held about Marechera, especially their expressions of psychic pain, longing, desire, frustration, boredom, and the material details of the correspondents’ private lives,” he continues (2002). Marechera, a scattered archive buried deep in the bloodwork and psyche of a people; an archive “dispatched after Marechera’s death from urban townships, rural areas, growth points, mining compounds, farms; places that only appear in the news during election season or moments of catastrophe” (2002) by school dropouts who went to fight in the war.

“In death, Marechera ruptures the view of Zimbabwe as a little corridor that starts in Harare and ends in Bulawayo,” writes Mushakavanhu. “The correspondents feel comfortable talking to Marechera. They know he will never scold them for what they say. He is ordinary like them, but constantly harassed by the state and its security apparatus” (2002). There is rumour of a circulating newspaper ad; a call for all who possess a Marechera story to share, “widely — and wildly”; “His official archive may be in Berlin. But his real archive is in you”.

Perhaps the state’s consumption of time — what Mbembe calls chronophagy (2002, p. 19–26) — has a feral inverse in the night: necroferality — a time eaten by the dead, returned half-digested, half-reborn. Necroferality is a temporality of refusal. It is non-linear, excessive, and uncontainable. It is history in decay, fermenting. Not just memorial but aftermath. If the state buries, the night exhumes. If the archive silences, the night shrieks, chants, stutters. Necroferality is not an absence of life, but an unruly form of afterlife — a form of time that bites back.

“That night all the lights I had known flashed through my mind.... My hunger had become the room,” writes Marechera in The House of Hunger. “There was a thick darkness where I was going. It was a prison. It was the womb. It was blood clinging closely like a swamp in the grass-matted lowlands of my life” (2003, p. 26).

One imagines the figure of the vampire in myth- not merely a figure of death, but of resistance. Literary scholar Jean Marigny (1993) notes that the vampire embodies fantasy’s central paradox — neither alive nor dead, it dwells in a threshold state that refuses categorisation. Grace Wood (2020) frames the literary vampire as a subversive figure that destabilises patriarchal binaries and asserts bodily autonomy through its refusal of assimilation. In Carmilla, J. Sheridan Le Fanu (1871) constructs a vampiric presence that blurs predator and victim, disturbing the clear demarcations necessary for archiving and legibility. Even within contemporary visual culture, figures such as Michael Hussar’s blood-slicked, ambiguous bodies (Velvet Noir 2023) attest to the vampire’s lineage as both anti-hero and anti-archivist. The vampire refuses daylight not out of fear but insurgency — rejecting truth-as-exposure and embracing an epistemology rooted in shadow, excess, and instability. To live in shadow, the vampire reminds us, is not to live in lack, but to live otherwise. It feeds on remains, lives in ruins, recoils from documentation, and thrives in the alleyways of collective forgetting. It keeps memory alive by leaking it, ingesting it, rendering it undead. After the media historian Norman Klein (2011), it is rare for a researcher to:

Where Mbembe names the archive as “proof,” as “authority,” as “instituting imaginary,” the night offers an unauthorised imaginary; the archive, after Klein (2011), as verb. This is the logic of cryptopoetics: a practice of engaging the archive as a haunted ruin, a plate of crumbs, a leaking grave, a breathless mouth.

The Chimurenga Library exemplifies this refusal. Itinerant and modular, it rewires the very concept of the archive through polyphonic disobedience. Often staged in colonial libraries in the West, it invokes “the archivist as a dissident poet,” to quote James Matthews (Rodwell et al. 2014). Books tear across time zones and epochs, vinyls carry ghost frequencies, periodicals deliberately misdate themselves. It is an archive that plays dead to survive.

In this shadow archive, time itself is rethought. Performance and visual studies scholar José Esteban Muñoz, in Cruising Utopia (2009), describes queer temporality as non-reproductive, future-fugitive — a mode that eludes productivity and linear progress. Nocturnal temporality, likewise, is anti-productive. It resists accumulation, rejects historical closure, and dwells instead in the cyclical, the recursive, the unruly. It is not revolutionary in the daylight sense of progress and triumph, but in its refusal to resolve. It is the temporality of aftermath, of echo, of things that linger without end.

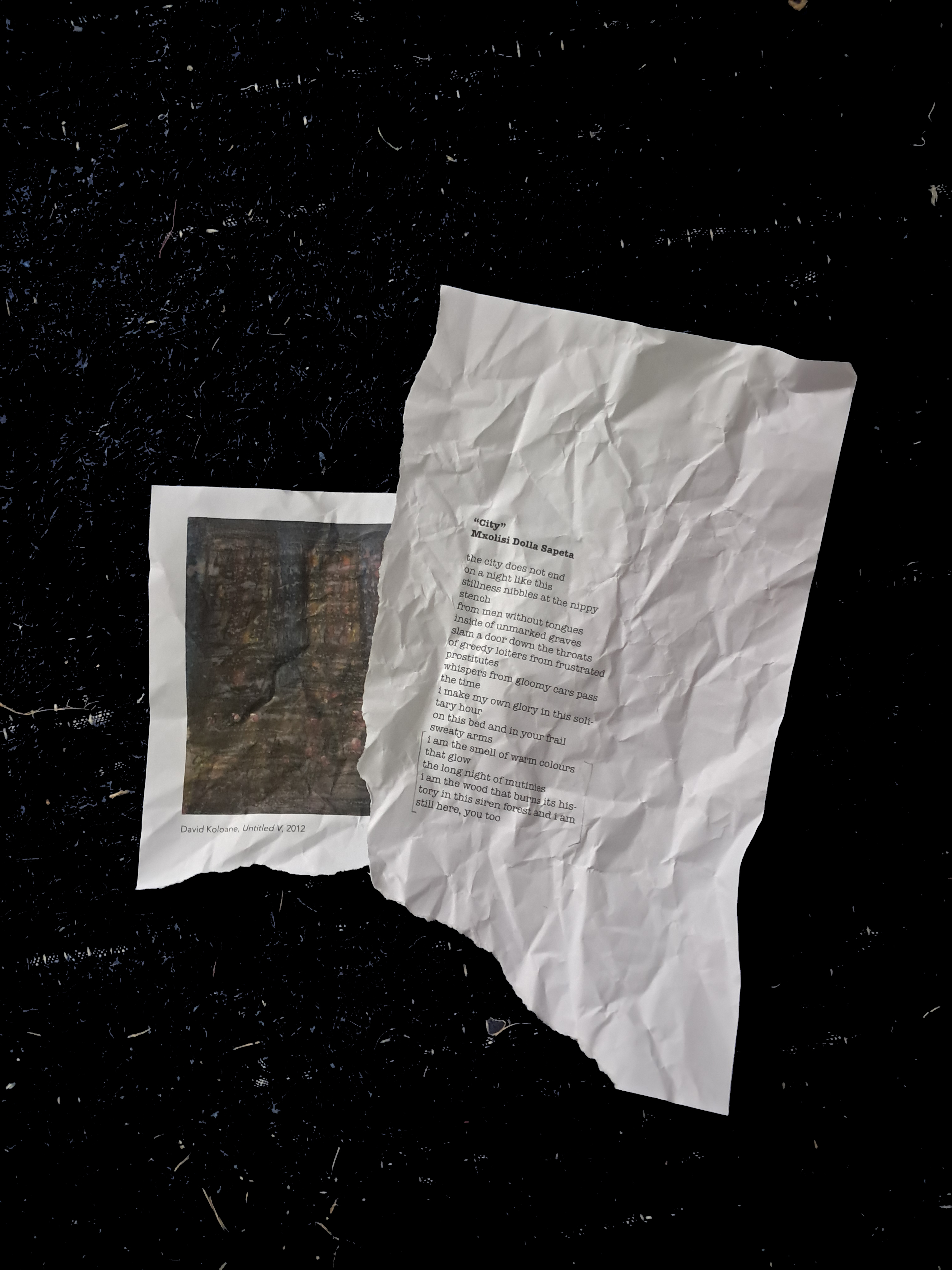

This is the temporality enacted in the aesthetic practices of artists like Dumile Feni and David Koloane. Their work does not oppose the archive per se, but operates within and against it, interrupting its drive toward classification and coherence. “Your education doesn’t allow you to understand the statement. You wouldn’t know” reads one inscription in Feni’s scroll. His restless lines and recurring figures do not settle into singular meanings, either, but remain volatile, provisional, always in excess of the page.

Koloane’s nightscapes are not representations of Johannesburg but invocations of its ungraspable atmospheres — dense with flicker, smog, and spectral motion. What binds their practices is not invisibility but opacity. These artists do not simply depict the night; they work with it, through it, allowing their art to inhabit a fugitive temporality that resists both capture and clarity. Their nocturnal aesthetics do not reject the archive outright but assert the necessity of an archive that can hold what cannot be explained; an archive that makes space for what survives through indirection, ambiguity, and the refusal to be fully known.

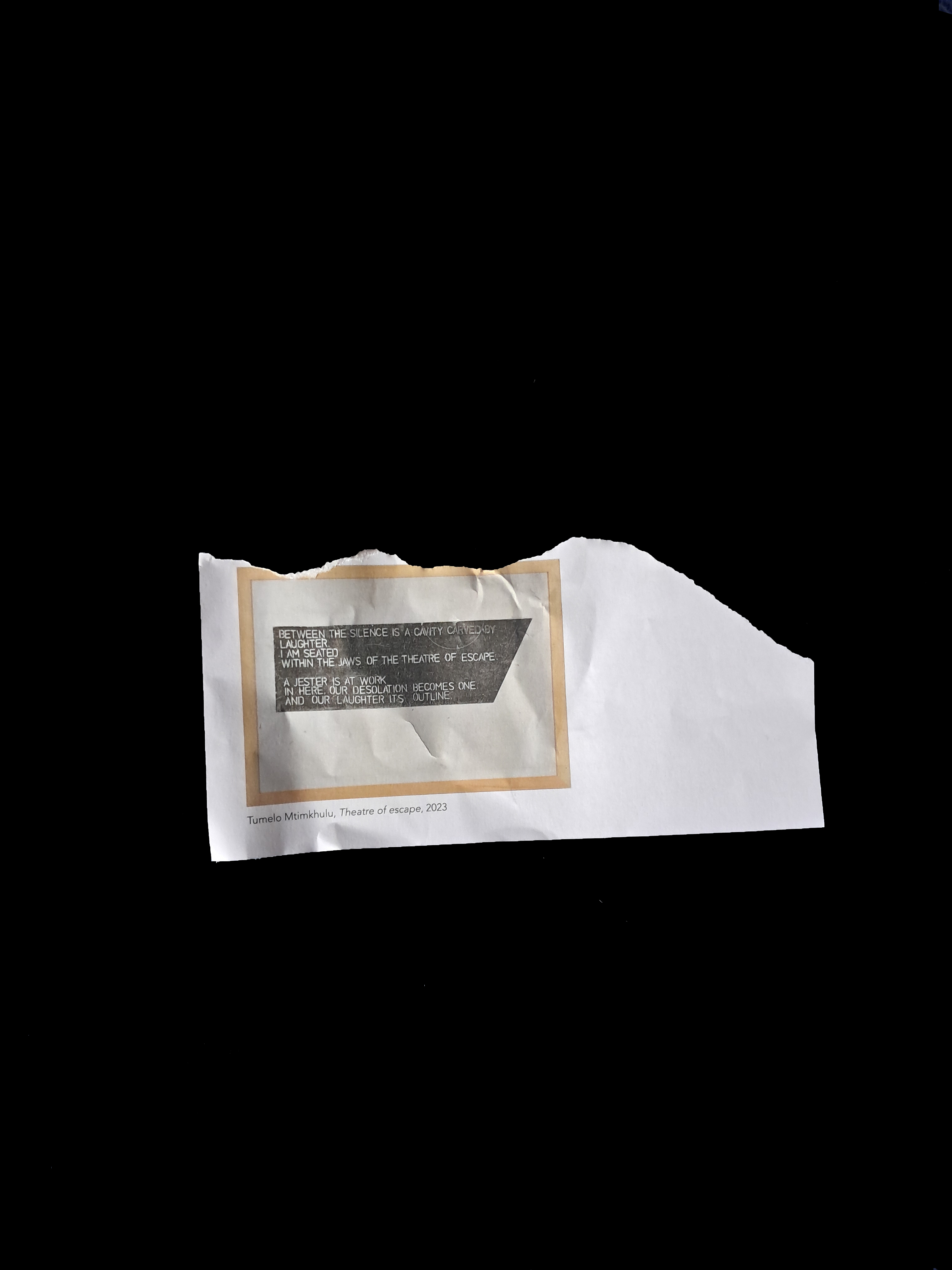

Robin Rhode’s chalk marks, ephemeral by nature, dissolve under rain, are erased by time — resisting permanence even as they momentarily transform urban surfaces into sites of aesthetic and political possibility. In garden for fanon (2021), Nolan Oswald Dennis gathers earthworms, contained in large glass orbs, and sets them to devour pages of The Wretched of the Earth. The digestion is literal, material, temporal: knowledge decomposes, disappears, is metabolised by another species. In both practices, the act of making is simultaneously an act of unmaking. They trouble the fixity of the archive, not by rejecting documentation, but by embedding transience, decay, and refusal into the very structure of the document.

This is not an anti-archival gesture, but a reconfiguration of the archive’s terms. These artists engage what Rebecca Schneider (2011), Professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, calls the performative remains — forms that endure not through stasis or fixity, but through repetition, transformation, and the memory of erasure. In Dennis’s work, this act is literal: the archive is not only consumed but composted. One could read this as a counter-gesture to philosopher Jacques Derrida’s archive fever, which he defines as an anxious compulsion to preserve that paradoxically contains the seeds of its own destruction (1996). But here, destruction is not feared; it is welcomed as a mode of redistribution and renewal — a slow epistemological fermentation.

This approach offers a radical reconceptualisation of inscription as fugitive marking — a writing that anticipates its own erasure while remaining felt. The archive, in this nocturnal mode, becomes less a site of preservation than of passing, staining, decomposing.

‘When I saw Dumile I asked him what had happened,’ said his friend, the former constitutional court judge Albie Sachs (Manganyi 2012, p. 130–31), recalling an encounter between the artist and a wealthy collector, where the artist intentionally destroyed a work that she’d wanted to buy by pouring ink over it:

Sachs reads the destruction of his own work as an act of self-sabotage, a missed opportunity, an act of ‘fleeing from success, [which] had some very deep roots that I was unable to understand’ (Manganyi 2012, p. 131), but what if such a flight could be recognised as an act of defiance, not unlike that of Marechera’s refusal to be packaged; an insistence on opacity in the face of a capitalist system that would seek to transform his work into commodity; to empty it of its political agency and insist on his economic subservience?

Since its founding, the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR) in Johannesburg has dismantled institutional approaches to art history, staging what it calls “reenactments as method” (2013). Their projects treat art history not as fixed inheritance but as an open score — something to be restaged, interrupted, remixed. In Passages (2011), they used collaborative installations to trouble historical authorship and linear time. In Xenoglossia (2013), they explored the mistranslation and mishearing of history as generative dissonance. Across these projects, programming loops and overlaps: events echo other events, temporalities stagger and stutter.

A jazz logic of call and response, improvisation, repetition with difference, and refusal of closure mirrors the recursive, fugitive methodologies of CHR. As Fred Moten argues in In the Break (2003), Black performance resides in the ruptures between sound and speech, noise and word — what he calls “the break.” This break is not a gap to be sutured, but a generative disruption. It opens the possibility for a different kind of knowledge — one that doesn’t resolve into coherence but stays in motion, in resistance.

One of the most intimate examples of nocturnal archiving — of memory as sound, unplanned, unrepeatable — is Moses Taiwa Molelekwa’s Darkness Pass (2004). The album, a double CD of solo piano recordings made secretly in 1996, was born of an urge to catch the night in the act of dreaming. Recorded in a locked SABC studio in Johannesburg, long after midnight, the sessions were not public performances or rehearsed recordings.

Producer Robert Trunz (2004) recounts lying on the studio floor, listening as Molelekwa played without pause for nearly three hours. The light was absent. The city hushed. Only the keys spoke. This was not a concert or rehearsal; it was a haunting in real time. No notation, no plan; just the sound of a world being conjured in darkness, for darkness.

Somehow, Trunz hit record. Molelekwa initially resisted the idea of releasing the work. He had just formed a band. He was forward-facing. Solo piano, to him, belonged to a more internal register — private, shadowed, unspeakable. And yet it is precisely this refusal that gives the archive its power - the delay, the silence, the secret. The fact that these recordings almost vanished — lost after his death, then rediscovered in safety copies by accident — only deepens their cryptopoetic charge.

The lesson is not simply to document differently, or archive more comprehensively, but to be there: in the studio, in the margins, in the cracks between rehearsals, in the off-hours where real transmission happens. To think with the night is to surrender the fantasy of total capture. Molelekwa’s Darkness Pass teaches us that the archive is not a fixed medium — it is an atmosphere, a residue, a fugitive presence that slips across genres and modalities.

This movement across forms is not incidental. It is part of the nocturnal method itself. Just as sound dissolves into silence, image dissolves into shadow. The visual artists we turn to do not work in opposition to the musicians who came before them, but in parallel — resonating across disciplines in their refusal of finality, their commitment to opacity. Like Molelekwa’s piano, their work emerges from the night and carries its logic: layered, elusive, resistant to closure.

This ethos finds powerful expression in the way dancer and artist Simone Forti transmits her work — not through written notation or digital capture, but through direct, embodied encounters. Her Dance Constructions are taught person-to-person, body-to-body, in the space of shared breath and timing. This mode of transmission — what Forti calls “passing through the body” (2003) — refuses standard archival legibility, insisting instead on presence, contingency, and the possibility of forgetting as part of the form. Like Forti, the nocturnal historian does not preserve from a distance but participates in the fragile moment of rehearsal, in the space where the work trembles, fades, flickers into being.

To cite the night is to summon its ethics, to let the night write back.